It is an arduous task to summarize in this article the course of the book in Argentina throughout the first half of the twentieth century. The theme, so rich and diverse, forces us to go through different spaces that include literature and the arts, antiquarian bookstores and others that once sold recently published copies, many of them a point of attraction today in the world of collecting of books, a fact that forces us to deal also with authors, publishers and printers.

And even, there are the auction houses, government and private institutions, scholars, collectors, and those who among them collect autographs and ex libris, in the next installment we will deal with the donation of María Magdalena Otamendi de López Olaciregui to the National Library, about 26,000 bookplates from its own collection. Addressing all these edges by illuminating their most relevant aspects is a mission that forces us to recognize that there will be capricious choices and accidental omissions. With due apologies, we begin this tour full of data and anecdotes.

For its writing we have resorted to various bibliographic sources referring to the history of the book -the classics and others-, to the catalogs of antiquarian bookstores and auction houses, of these especially when they have offered the great libraries; we have more than six hundred catalogs published throughout the entire twentieth century. We also draw on the publications of the Buenos Aires Institute of Numismatics and Antiquities, of the Society of Argentine Bibliographic Studies, of ALADA (Association of Antiquarian Booksellers of Argentina), of the Graphic Arts Section of the Argentine Industrial Union, of the National Library, of the Archive General of the Nation and the Library Research Center of the UBA. In addition, we flower the text with anecdotes harvested in just under thirty years of tasks linked to letters, arts and crafts, and we especially consult bibliophiles and colleagues, antiquarian booksellers.

We are encouraged by the will to reflect the harmonious concurrence that has taken place throughout the twentieth century between public bodies and private activity around the book. Collectors have enriched the public heritage with numerous donations, patronage, personal commitments and various efforts, contributing to the evolution of museums and institutions. Joint efforts between both actors -the state and the citizens- is a rule that bears good fruit, and from reading so many examples we are encouraged to imagine a more efficient future even in the common task of studying and preserving this heritage with future generations in mind. to come

We begin this work with some brief reflections on private libraries and their characteristics.

How are private libraries born?

They arise from a book, from an exciting reading that leads us to the next, and another, and another. This is how the process begins and in an unexpected moment, one is surprised to notice that the first piece of furniture that houses the books is overflowing.

The protagonist of this experience can be a lawyer, a historian, a scientist, a poet, a baker, a blacksmith... A specific profession is not required, it is only necessary to have discovered the pleasure of reading and to have an open mind to get excited, learn, doubt, question and even laugh immersed in the evolution of a printed text. And there are also those that are born and grow in the heat of the studies carried out by their owner, a specialist who, in his daily work, built his reference library. In these cases, surely we must talk about a regular visitor to second-hand bookstores, who knew how to reap good prizes in his frequent searches through sale tables and in the most remote places of each store visited, but who also deducted the list price in the releases of those books that were "necessary", and even encouraged to buy some desired titles in catalogs of antiquarian booksellers, and in auction rooms. Luis Lacueva, a dean among antiquarian booksellers, recalled in 1997 that he frequented sixty libraries of researchers and scholars. [1]

Platelet edited by the Argentine Bibliophile Society (1993) with small portraits of large libraries. (Hilario Library)

Julián Cáceres Freyre also did the same in “Libraries that I have known as a student and researcher”, a beautiful plaque edited by the Argentine Society of Bibliophiles; among others, it brings together data and anecdotes from those formed by Félix Outes (1878 - 1939), Francisco de Aparicio (1892 – 1951) -after his death, acquired by the National University of Rosario-, Milcíades Alejo Vignati (1895 - 1978) - Without personal fortune, he had formed a library on Patagonian travelers only comparable to the Armando Braun Menéndez, he affirms, Ricardo Lafuente Machain (1882 - 1960) and Carlos A. Moncaut (1927 - 2008), whose collection was dispersed in intense auction days organized by Casa Saráchaga years after his death; all of them protagonists in their disciplines and owners of important reference libraries.

At the other angle are those who are passionate about rare and curious books who are dedicated to collecting and studying them. And it does not matter the number of collected specimens, but their qualities. A good bibliophile, we are now talking about this character, looks for first editions in general from the incunabula, qualifying as such those published from the origin of the printing press (around 1450) until the end of the fifteenth century, and from there to here, to all good edition that deserves to be added to your library.

Without intending to write an apology, let us say that the true bibliophile has a particular sensitivity and does not go through life accumulating volumes without rhyme or reason. He conducts bibliographical research, studies the author, the publisher, the printer, the illustrator and in each copy, the state of it, and the binding it has. His searches have a meaning that he was building to shape the desired and possible library. Of course, in addition to the collected titles, we insist, he is very meticulous with each copy, including some of them rebinding them with famous European masters of this trade, and others going, for example, to the workshop of the Sisters of the Divine Face located in Parque Centenario, in Buenos Aires, in front of the Argentine Museum of Natural Sciences.

Both library profiles have defined features and promise disparate destinations. It can be very complex to find a new home for the study ones, especially if you intend to preserve them as their founders built them. Public institutions are reluctant to incorporate these sets for numerous reasons: from the scarcity of space, the repetition of copies already available, the theme or the lack of operational capacity given the thousands of volumes to inventory and manage their use. And if antiquarian bookstores do not find those special titles that give an expectation of profit to their acquisition, they are usually discarded and go through the worst of endings, which hurts us so much just imagining it. It is that these libraries, in general, are made up of popular editions and contain knowledge and outdated fashions, a real problem for their preservation. Those collected by bibliophiles, on the other hand, can end up in a public repository through a free donation from their creator or heirs, or return to the market through an antiquarian book dealer or an auction house. In the first case, it will surely remain united, while, in the other two hypotheses, it will be dispersed with new owners who will treasure their acquisitions with the same passion and commitment as their previous owner.

1900 – 1924

We begin this journey with the first twenty-five years of the 20th century, just when our country was celebrating its two centenaries: the May Revolution (1810-1910) and the Declaration of Independence (1816-1916).

These events generated a wide series of actions aimed at showing a prosperous and receptive republic of international capital and human resources. In such a scenario, the book industry advanced at a good pace and collectors toured Europe eager to obtain historical works and the most innovative testimonies of the artistic currents in vogue.

Here in Buenos Aires, the century began with the transfer of the National Library to a building located on Calle México 564, in the heart of the Monserrat neighborhood, initially destined for the National Lottery.

Former headquarters of the National Library, today installed in the building designed by the architects Clorindo Testa, Alicia Cazzaniga and Francisco Bullrich, with its entrance at 2502 Agüero Street, always in the city of Buenos Aires. Photography: https://turismo.buenosaires.gob.ar

It was in this period that the world of letters together with the arts experienced a disruptive time. The so-called avant-gardes promoted significant changes in cultural production, leaving behind the past even in its most qualified manifestations. Immersed in this current of change, there were not a few Argentine creators who captured these new airs in their European sojourns. Pettoruti, Xul Solar, Jorge Luis Borges, his sister Norah and Oliverio Girondo, among others, ventured down such paths. His works are preserved in important national and international public and private collections, and three of them, Borges -he was director of the National Library-, Xul Solar and Pettoruti, give life to two Foundations that protect and disseminate their legacies with their careers.

This plethora of intellectuals gathered around the magazine Martín Fierro (1924 – 1927). They were looking for aesthetic modernization. His gaze was directed towards the new airs of the European avant-garde: ultraism, expressionism, futurism, cubism, Dadaism and surrealism that broke into literature, visual arts, music, architecture, theater and art. cinema. That periodic publication was a renewing voice that was raised “in the face of the funeral solemnity of the historian and the professor, who mummifies everything he touches”, as Oliverio Girondo put it in his Manifesto published in number 4 of Martín Fierro.

Among its antecedents we must mention two Spanish magazines -Los Quijotes and Grecia- and at least another couple of local periodicals: the mural magazine Prisma -there were two numbers distributed between December 1921 and March 1922 through stickers on the walls of Buenos Aires- and a triptych entitled Proa, whose three numbers were published from January 1921 to February 1922. At that time, the project that would give life to the magazine Martín Fierro was germinating with its director as inspiration; we refer to Evar Méndez, poet and great cultural manager.

Simultaneously, Buenos Aires cradled another center of artistic and literary creation, a movement that was centered around Boedo Street, whose members practiced a militant commitment, rebelling against the unjust social situation. In these first decades of the century, the modernization of the country was not exempt from contrasts, including the advance of large pockets of poverty. Such a dichotomy was observed by art and literature that echoed a growing discontent, also fueled by the rejection of the First World War and even the Russian Revolution. Groups of anarchists and socialists -whose leaders were mostly European immigrants-, pacifists in general, led a movement to reject social injustices that in Buenos Aires erupted in the Tragic Week (1919) initiated by the claim of the workers of Vasena Workshops, whose repression cost the lives of more than seven hundred people, and which in the south of our territory resulted in another event with a sad ending, the so-called Rebel Patagonia (1920-1922), or tragic, which doubled that number of victims.

Sensitive to these events, a group of writers and artists identified with the name of Boedo was born in the Argentine capital, whose primary organ of expression was the magazine Los Pensadores, directed by the Spaniard Antonio Zamora. The publication, aimed at a popular reader -it had a very accessible cover price-, brought together a hundred works written by international and local authors, all committed to the most punished and vulnerable sectors. Los Pensadores was followed by another magazine, Claridad, also directed by Zamora, whose spirit Leonidas Barletta was well able to define when he stated: «We held two fundamental questions: that art had a social function and that, if art did not take care of the people, the town did not have why to take care of the art».

At that time, the country received waves of immigrants -Europeans in general, and mostly Italians and Spaniards- who led a very striking phenomenon by adopting the figure of the gaucho as an emblem of the new homeland. In full decline in his natural environment -the countryside-, that cowboy rider woke up as the protagonist of an urban movement to revalue his customs; Traditionalist centers were born accompanied by a greening in the trades that dealt with their Creole accoutrements. Similarly, literature and the arts ventured into the rescue of native cultural identities, already in dialogue with other international currents. In this line we mention the creation of Ricardo Güiraldes and Alfredo González Garaño of the Caaporá ballet, a Guarani legend conceived from an Americanist aesthetic, but renewed in the light of contemporary art. The work was admired by Nijinsky, and although it was not possible to carry it out, the paintings of the costumes, and the sets and decorative objects that were intended to be used are preserved; They were exhibited in 1917 in Buenos Aires, at the Salón de Acuarelistas, and in 1920, in Madrid, awakening in the Spanish critic José Francés a very hopeful judgment: “They are demonstrative proof that Hispanic Americans are going to have a modern art of their own, deeply rooted in national elements.

Güiraldes wrote one of the most important titles of Argentine literature, Don Segundo Sombra, and in his small payment, San Antonio de Areco, he advanced the idea of promoting this city as the cradle of the gaucho. [2]

There, in Areco, one of the most important printing presses of the 20th century operated, created in 1902. Francisco A. Colombo was its architect, for Ricardo E. Molinari, perhaps the maker of “the most beautiful books that have been printed in Argentina”. The work of Ricardo Güiraldes came to light in his craft workshop, starting the Xaimaca series in 1922 with a print run of two hundred copies. Four years later, the aforementioned Don Segundo Sombra gave the consecrating accolade to the author and the printer; there were two thousand copies and the edition sold out in just thirty days. In the same 1926 the second was published, already with five thousand copies. Colombo was a thorough printer of books for bibliophiles, attentive to the typefaces, the titles, the initials of the chapters, the margins, the quality of the paper, the intensity of the inks... He became an emulator of the masters Renaissance printers in the middle of the humid Pampa until, in 1929, he moved his workshop to Buenos Aires and in the cosmopolitan city reached the zenith of his production, illuminated by true milestones, such as the version of Martín Fierro illustrated by Adolfo Bellocq -published by the Association of Amigos del Arte- and in 1935, the Facundo with etchings by Alfredo Guido, this one for the Argentine Society of Bibliophiles. In Guillermo Palombo's opinion, “a bibliophile's work: restricted circulation, printed on large paper, illustrated with original plates and artistically decorated with typographical elements”. [3]

From another business perspective, with works aimed at readers in general, although also seeking to captivate the more educated public, the Argentine publishers that had been born in the second half of the previous century continued their development incorporating new technologies and disputing the signature of the authors. more consecrated. Among them, Guillermo Kraft, Jacobo Peuser, Lajouane -also owner of his National bookstore-, Imprenta Coni and Compañía Fabril Sudamericana, to which other labels were added, such as the Atlántida publishing house, owned by Constancio C. Vigil, with its Atlántida Billiken libraries. and its Antorcha collection, the Cooperativa Editorial Buenos Aires, created and directed by Manuel Gálvez, and, among others, La Novela Semanal, by Miguel Sans, and the Kapelusz and Tor publishing houses, and the Argentinian Graphic Workshops of L. J. Rosso. Juan Carlos Torrendell (1895 – 1961) with his bookstore and publishing house Tor “flooded” the market with inexpensive books published from 1916 onwards, printed on newsprint and with glossy paper covers. Another firm that was born around these years and advanced beyond the middle of the century is that of the brothers Francisco and Mario Mercatali, from whose press came out in 1917 one of the most sought-after books in Chile today, Inquietudes sentimentales, by the poet Teresa Wilms. Montt, with illustrations by Gregorio López Naguil.

In those years, two great Argentine authors directed two collections of books, both started in 1915, we refer to José Ingenieros and Ricardo Rojas; the first responsible for the collection La Cultura Argentina (1915 – 1925) and the second, for La Biblioteca Argentina, which included twenty-nine titles. Rojas seeking to exalt the Creole figure while promoting to deactivate that foreign influence that could blind the local, and Engineers, rescuing the contributions made by immigration, and between own and newcomers, with the determination to choose the most meritorious titles. Another hierarchical project was the collection directed by Julio Payró, La Biblioteca La Nación. In all of them we find authentic classics.

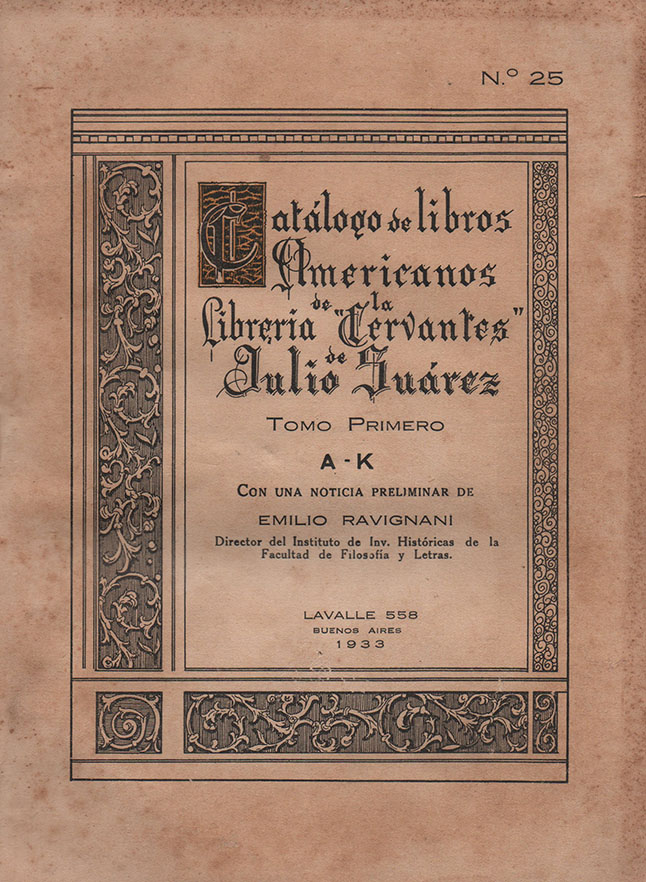

And contributing from the commercialization, the bookstores extended in the Buenosairean geography. As you can imagine, there were those dedicated to modern books, the novelties published here, and those that came from Europe, and those that dealt with ancient books. Among these we point out the Cervantes bookstore, owned by Julio Suárez, a Spaniard who arrived in 1906 as a stowaway and here acquired the trade of book seller. In 1914 he took a small step and bought the Perfecto García bookstore, a tiny store from where he forged a great career; he became the great bookseller of his time. (4) His bookstore represented a study center where the scholars of our past went daily to consult books or to talk about them, affirmed Domingo Buonocore -the great Argentine bibliographer- and in his gatherings he summoned among many, Agustín P. Justo, Emilio Ravignani, Antonio Santamarina, Ernesto H. Celesia, José Torre Revello, the brothers Alejo and Alfredo González Garaño, Rafael Alberto Arrieta, José Luis Busaniche and Julio Noé. The Tomás Pardo Bookstore -a surname installed in Buenos Aires in the field, but we clarify that Tomás was not a relative of the founders of the homonymous house- also advanced in this field; We have a bound volume with his first fifty Bibliography lists, published between April 1922 and June 1929. Casa Pardo, we will share more information about it later, was one of the most prestigious in the country, extending to other antiquarian items. And the Colegio Bookstore, at the time owned by Cabaut y Cía, on the corner of Bolívar and Alsina, continued its trajectory.

In reference to the bookstores of modern editions and novelties, the most outstanding was El Ateneo, by the Spaniard Pedro García (1885 – 1948), an entrepreneur who also started with a small business and came to distinguish himself as the most stocked house in his genre with a corps of runners that traveled all over the country. Today we recognize it as the most thriving bookstore chain -Yenny- and publishing label, El Ateneo, owned by the brothers Eduardo and Ricardo Gruneisen, important art collectors.

There were also author editions, such as the Catalog of the American Library, by Manuel Y. Molina, printed in 1917. The owner of that collection recounts in the first pages some testimonial impressions about the origin of his collection. Molina had an important library, verified by his catalog with more than 2,000 detailed books throughout 261 pages.

Gardner Library Sale Catalogue. (Hilario Library)

In the daily walk the existing collections were increased, some were born and others were dispersed in the auction houses; This was the case at the beginning of the century with the library of Andrés Lamas (1817 – 1891), which in 1905 passed through an auction room in Buenos Aires. The books not sold on that occasion, about 8,000, were offered in 1917 to the Uruguayan government, which today preserves them in the National Library of Montevideo. In the Official Archives of both countries, two separate Lamas collections are kept with thousands of prints and historical documents, in Argentina with an edited catalogue. The library of the Scottish Gorge Alexander Gardner, the researcher of the pictographs of Cerros Colorados, in the north of Córdoba, studied and reproduced some time later by the Norwegian Absjörn Pedersen, also passed through the hammer of an auction house. Gardner had returned to his land, Pedersen told us around 1985, having previously left the original of his essay to be published in Argentina, but local delays caused it to be edited in 1931 by the University of Oxford.

The destination of those great libraries -also of the collections of works of art and historical objects- could well be a bookstore or antique dealer, an auction house, or a public institution, sometimes created to receive so many treasures. This was the case with the donations of Isaac Fernández Blanco (1862 - 1928), who ceded his collections, including the library, to the City of Buenos Aires to form a museum that should bear his name, today the Museum of Hispanic American Art, I quote in the 1422 Suipacha Street, expanded with the collections of the architect Martín Noel and numerous other donations, and also with the library of Oliverio Girondo and Norah Lange, who sold the couple's old house to the Municipality, a place of unforgettable meetings, now in full swing. restoration process.

The close link between books and works of art formed by collectors since colonial times continued throughout this century until almost the end of it. This is how Marcelo E. Pacheco expressed it in his work Collecting Art in Buenos Aires. 1924 – 1942: “Books, archives and documents together with the iconography of someone like Alejo González Garaño; books from the 19th and 20th centuries among the sets of oriental art and European painting from the 1800s by Francisco Llobet; more than two thousand volumes of history, literature and law coexisted on Santa Fe street with the Toulouse-Lautrec de Santamarina. Among the rentier middle class, the national library of five thousand volumes of Eduardo Mariño was formed, together with travelers from the 19th century and memoirs from the time of Rosas. [5]

Later we will include other names that will enrich this short list; many more libraries were born and kept alive in this half century driven by authentic collectors.

1925 - 1949

Argentine literature -we announced it- was advancing along different paths, centered around two opposing groups whose axis was the arteries of the city of Buenos Aires: Florida and Boedo. Among these, the Artists of the People, a group of engravers who created their works as a claim for social issues, also acted with singular relevance. One of the members of Boedo, Álvaro Yunque, defined both perspectives in this way: “those from Boedo wanted to transform the world and those from Florida were satisfied with transforming literature”. The former defined themselves as revolutionaries and the latter as avant-garde. In line with this synthesis, Evar Méndez, director of Martín Fierro, maintained that, based on this publication and movement, "the country is written and painted in a different way."

Beyond jealousy and rivalry, this golden age is today a matter of study and attraction for historians of art and letters, for collectors and cultural institutions in Argentina and abroad. The works of its most outstanding authors are part of museums, archives and libraries; their titles are sought in the first editions preserved in their original states, with the publisher's bindings, without marginal writings, except those made by their authors or colleagues, sometimes true treasures. And in addition to the books, there is special interest in the originals created for their illustration, as well as in the correspondence that linked the authors, editors, critics and others.

Argentina was going through the so-called interwar period when it experienced a notable rise in literacy rates; over 80% nationwide, and over 90% in the city of Buenos Aires. This process was reflected in the increase in sales of newspapers, magazines and books with highly successful popular editions. The morning paper Crítica, for example, reached over 350,000 copies and published a weekly with texts by Ulises Petit de Murat and Jorge Luis Borges, the Multicolor Magazine, a surprising publication for its texts, illustrations and design. [6] Another milestone in local publications, Ricardo Rojas' work El santo de la Espada, on the life of José de San Martín, was published for the first time in 1933 and reached a record edition of one hundred thousand copies.

Natalio Botana, owner of Crítica, formed his personal library that occupied the first floor of the luxurious villa “Los Granados” -where Siqueiros painted his mural- of him, in Don Torcuato. Library that Pablo Neruda in his book I confess that I have lived qualifies as “fabulous”. And it was. Number of old books that he bought by cable at European auctions, incunabula, and works on history, geography, philosophy, mythology, travellers... Botana died in 1941 and twelve years later, in 1953 what remained of that collection was auctioned off -1765 lots, many of them between 6 and 10 volumes- in the Sales Hotel of Luis Guaraglia.

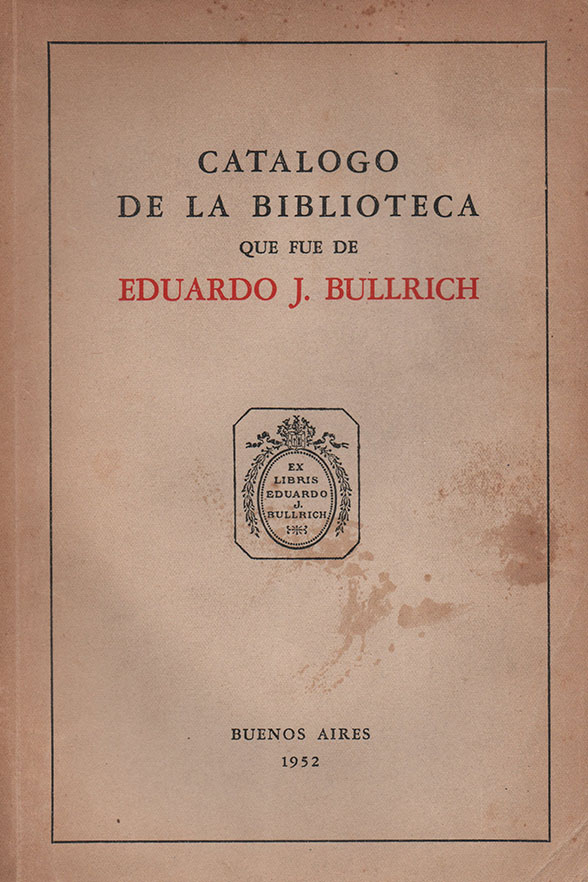

Although with the indicated indicators it is possible to speak of a spring in the sector, the truth is that written paper began to compete with sound films, radio, and records together with the phonograph. It is that the new habits spread throughout the country without a single corner remaining away from those inventions, and surprisingly today, already in those days people began to talk about the death of the book... However, the habit of reading advanced also penetrating society as a whole with diverse offers, aimed at the mass public and the most demanding readers who were looking for a book with art. Among these, the Society of Argentine Bibliophiles was created in 1928 following the guidelines of a similar French institution. [7] The members, here limited to one hundred, selected the titles, illustrators, publishers and printers, and published works in short runs of one hundred and five copies, each one being “nominative”: with the printed name of its recipient. Among its first partners we find the owners of important libraries; We mention Victoria Ocampo, Elisa Peña, Ricardo and Teodoro Becú, Lucas Ayarragaray, Eduardo J. Bullrich, Jorge Beristayn, Félix Outes and Ricardo Lafuente Machain, to whom were added Mariano de Vedia y Mitre, Carlos A. Mayer, Abel Chaneton, the brothers Alfredo and Alejo B. González Garaño, and Horacio Zorraquín Becú. The first work was published in 1935, Facundo illustrated by Ángel Guido and printed by Francisco A. Colombo. Three years later he was succeeded by Romances del Río Seco, by Leopoldo Lugones.

That 1928 will also be remembered for the 1st National Book Exhibition, organized by Rómulo Zabala, Manuel Conde Montero and Juan Canter (1860 – 1924); where the latter, a prominent bibliophile, exhibited a striking set of prints of Foundling Children. It is known that Canter's collection - in the vast majority, about 5,500 items - is kept in the Library of the Colegio Nacional Buenos Aires, where it was donated, and a small part was inherited by his son of the same name, also a prominent Argentine intellectual.

Willing to review the fate of the most important private libraries, that of Jorge Beristayn (1894 – 1962) deserves a special paragraph; A great bibliophile, painter and musician, he transcended for owning more than a hundred incunabula, as well as being an exquisite collector of works of art, ceramics, porcelain and musical instruments. Regarding his library, exceptional in the South American sphere and, without a doubt, a reflection of his knowledge of the first stage of the printing press, Hans Peter Krauss wrote -the most famous bookseller of the second half of the 20th century at a universal level- who, knowing of the possession of an incunabulum in particular, edited in 1462, he traveled to Buenos Aires together with his wife, and although the attempt was unsuccessful, he recalled in his memoirs Beristayn's chivalry and friendliness. In 1937 this bibliographer had offered his collection with one hundred and fourteen incunabula to the national government, which rejected the proposal. Seventeen years later, Krauss received that fascinating list of books from Argentina, and surprised moved to the south of the continent where he acquired some of those treasures, although not the most desired. [8]

Argentina had those peculiarities, enriched by works of universal relevance that had arrived as a result of the actions of its collectors. Similarly, our society received the most outstanding artists and men of culture in general. Among others, Anatole France and Vicente Blasco Ibañez had visited us in 1910, José Ortega y Gasset (on three occasions, 1916, 1928 and 1939), Marcel Duchamp (1918-1919), Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (in 1926 and 1936), Le Corbusier (1929), Federico García Lorca (1933-1934), and in full publishing boom, already in the 30s, it was one of the destinations chosen by exiled Spanish republican intellectuals during and after the Civil War (1936 – 1939) . Although they found here a populous Hispanic community mostly favorable to their cause, the truth is that they also had to deal with the political powers that, on the contrary, were suspicious of their ideology and hindered their entry into the country. [9]

Among the Spanish countrymen already settled, we highlight three of them, protagonists of the book industry in the midst of the arrival of the Republican diaspora. We are referring to Gonzalo Losada, former manager of the Espasa – Calpe subsidiary, who launched the Espasa – Calpe label in Argentina in 1937 and a year later, Editorial Losada; Rafael Vehils, who gave rise to the Editorial Sudamericana with the contribution of intellectuals and representatives of the local upper bourgeoisie, and Pedro García -already mentioned-, founder of El Ateneo, an active collaborator of the new publishers through his distribution network and from your bookstore.

The expansion of this industry benefited from the contribution of prominent Republican personalities; Guillermo de Torre began to work together with Losada -he shaped the Austral collections, from Espasa-Calpe Argentina and the Biblioteca Contemporánea [10], from Losada- and Antonio López Llausás did the same with Vehils; together with de Torre, both experienced editors in the peninsula.

Two graphic arts professionals trained at the Milan Book School, Ghino Fogli (1892 – 1954) and Attilio Rossi (1909 – 1994), also came to Buenos Aires. The first created a printing press in 1928, the Atelier de Artes Gráficas “Futura”, of which a few years later he was its sole owner; exquisite typographer, we owe Fogli wonderful editions. Let us remember El Motín de los Artilleros, by Armando Braun Menéndez, a paradigm of luxury editions, and Martín Fierro y la Vuelta, with illustrations by Tito Saubidet, another masterpiece of Argentine graphics, both for Viau and Zona. Fogli hired Rossi as designer typographer, a born innovator who arrived in 1935 and left his mark first in Fogli's Atelier Futura, and then in Espasa – Calpe and in other printers. Let us remember that Attilio Rossi collaborated with the graphic composition and design of the urban photobook Buenos Aires 1936: photographic vision, by Horacio Coppola, an innovative title in our environment.

By the 1940s, Buenos Aires had become the publishing capital in the Spanish language, as a result of the literary creation of local authors together with the intellectual contribution of exiled Republicans, but also with the enterprising strength of those publishers, Republicans and Francoists; all incorporating themes and voices enriched by international dynamics, with the impact of World War II (1939 – 1945) and its sequels of all kinds.

The year was 1941 and a new space for selling books was inaugurated in Buenos Aires, built in the backyard of the Cabildo. The initiative was born in the then mayor, a historian and bibliophile, Carlos Alberto Pueyrredón (1887 – 1962). That open-air fair first brought together prominent antiquarian booksellers who set up their branches there in the form of kiosks, soon replaced by other less pretentious, more popular professionals, giving it the profile that made the place famous until in 1960 it was moved to Plaza Lavalle, in front of the Courts, where there are still several businesses dedicated to this activity today.

Work of Raúl M. Rosarivo. Edited for the II Congress of the Argentine Graphic Industry. Buenos Aires. 1964. (Hilario Library)

A couple of years later Editorial Huarpes was born, guided by the Jesuit historian Guillermo Furlong and with capitals from Miguel Stragno and Francis O'Grady, a great patron of Furlong's work. The publishing house was operationally led by Luis Trenti. Among its merits we highlight the layout of the master of graphic arts Ghino Fogli. Its catalog transcends titles that today continue to be of first consultation, such as the work Origins of typographic art in America; especially in Argentina, by Furlong, printed by Kraft under the direction of Raúl M. Rosarivo (1903 - 1966), another master of the trade, teacher at the National School of Graphic Arts and at the Argentine Institute of Graphic Arts, and author of numerous works referring to the "divine typographic proportion" and the history of the book. In the same range of relevance we include the series Argentine Colonial Culture, whose first title was Argentine Libraries during the Spanish domination, where Furlong identified one hundred and eighty owners of books and libraries in colonial times settled in these lands.

In 1943, the Argentine Book Chamber organized a book fair on the final block of 9 de Julio Avenue -between Cangallo (today President Perón) and Bartolomé Mitre- that remained open for thirty days. As a reminder of that event, Juvenilia, by Miguel Cané, illustrated by Caribé, was published. With a very accessible cover price, 35,000 copies were released. Another highly successful initiative was the edition of a daily Bulletin that was printed in front of the public with the novelties of the fair. The López printing press had brought one of its machines to the delight of the curious, and in "adherence to the First Argentine Book Fair" it published a tiny pamphlet entitled Little History of Printing in America, with a beautiful layout, and the text by Félix of Ugarteche.

A memory of the 1943 book fair in Buenos Aires. (Hilario Library)

Among the most thriving companies that made up the Chamber of the sector, Sudamericana had acquired the Colegio's Bookstore in 1940 and concluded the decade with a policy of opening subsidiaries abroad, such as Hermes in Mexico and Edhasa in Barcelona.

Another publishing house that made steady progress through this quarter of a century was Emecé, created in 1939 with a solid Galician presence - Arturo Cuadrado and Luis Seoane worked there in the beginning - and financially supported by the contribution of the Braun Menéndez family. Its extensive catalog brought together various collections, giving it a strong boost with the incorporation of Bonifacio del Carril in 1947. Among its milestones, it is worth highlighting the Seventh Circle collection of police novels, directed by Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares between 1947 and 1955, and the publication in 1951 of Death and the compass, by Borges, beginning the edition of his works. In addition, they capitalized on the success by acquiring the commercial rights for their Spanish editions of The Little Prince and the novel Papillon. Both pillars of this publishing house, Armando Braun Menéndez (1898 – 1986) and Bonifacio del Carril (1911 – 1994), formed the troupe of the most qualified collectors, creators of important libraries; the first of Chilean origin but closely linked to Argentina where he spent a good part of his life. He was a founding member of the National Academy of Geography of our country, and donated the collected books -one of the most important collections here formed on the subject of travelers- to the National Library of Chile and the Argentine Academy of History. Bonifacio del Carril, a full member of the National Academy of History and Fine Arts (he presided over it three times), was also a prolific author, with important contributions to the iconographic study of Argentina since colonial times. His library was dispersed in a public auction already in the twenty-first century with an important catalog made by the specialist María Marta Larguía Avellaneda.

In 1940 Buenos Aires experienced a relevant event in the cosmos of the oldest editions, we refer to the Great Book Exhibition -just under seven hundred copies were exhibited, including one hundred and sixty incunabula-, held in commemoration of the five hundred years of the creation of the printing press. The exhibition, quite an event, was accompanied by a catalog that is still a matter of consultation today, written by the bibliophile Teodoro Becú (1890 – 1946). The most outstanding collectors, booksellers and institutions participated. Becú himself had an important library, whose three-volume catalog includes comments by him; it was designed by Mario Rosarivo and printed after his death.

At the institutional level, a civic-military coup d'état in 1930 overthrew the government of the radical Hipólito Yrigoyen, elected by popular vote - still only male at that time - in his second term, and giving rise to the so-called "infamous decade". General José Félix Uriburu led the insurrection that was supported by the conservatives and the radical anti-personalist sector; Likewise, prominent intellectuals did it, among them, Carlos Ibarguren [11], Juan Carulla, José María Rosa, Leopoldo Lugones and the brothers Julio and Rodolfo Irazusta. The press played an important role in Yrigoyen's fall. This was recognized by the newspaper Crítica in an editorial: “In Crítica the civil leadership of the revolution was centralized”. But the pro-fascist profile of the new government soon isolated it and it had to call national elections at the end of 1931. The polls gave power to General Agustín P. Justo (1932 - 1938), the candidate of a coalition that brought together the forces that destabilized Yrigoyen, along with independent socialism. Under the impulse of his son Liborio, Justo was an exquisite bibliophile; A regular attendee at book auctions and a faithful reader of the catalogs printed by local and foreign antiquarian booksellers, he knew how to put together one of the most important libraries formed in the country, always with the advice of his faithful friend, the great bookseller Julio Suárez.

In this quarter of a century, Argentina experienced another political episode that changed its course; we refer to the public irruption of a leader who is still linked to the destinies of the country, General Juan Domingo Perón (1895 – 1974). In 1943 he was part of the Revolution that ended the so-called Infamous Decade and joined the government until in 1945 he was displaced and detained on Martín García Island. But a great popular mobilization, on October 17 of that year, placed him in the central stage of politics and freed, he headed the triumphant presidential formula. On June 4, 1946 he assumed the presidency of the Nation. His wife, María Eva Duarte (1910 – 1952), Evita, played an enormously important role in his government. There were two periods, the last one cut short by another coup, in September 1955. The Peronist government consolidated the editorial development of our country; willing to promote national industries and attentive to the dissemination of the benefits of its leaders, he built a communication model that was reflected in books, newspapers and magazines, with strong pressure on intellectuals and businessmen who were part of the opposition .

Returning to the figure of Agustín P. Justo and his library, María Teresa Giraldes wrote in La Prensa, Justo had intended to open it to the public and turn it into a study and research center - among the papers in his archive a plan was found classification - but his sudden death frustrated the project. The truth is that, without sufficient resources to preserve it, “at first his heirs hoped that the national government would show an interest in retaining it in the country. But the expected interest did not materialize. [12] Guillermo Palombo reminds us that, in 1943, with the national authorities that emerged from the coup d'état that overthrew Ramón S. Castillo, they listened to the advice of the Executive's legal advisor, Dr. Carlos Ibarguren, who ruled negatively on his purchase. "Political prejudices were more powerful," Palombo assured us. We will talk later about his fate.

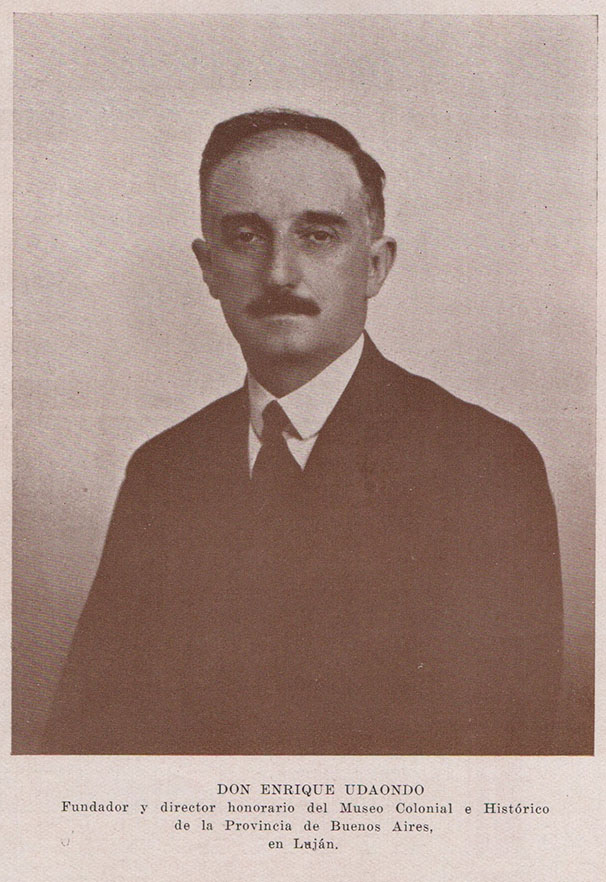

Private libraries, perhaps it is worth insisting on now, were formed for the simple love of books, and because they were an essential reference source for specialists from the most varied disciplines. We mention two examples, those collected by Adolfo Saldías (1849 – 1914) and Enrique Udaondo (1880 – 1962), both historians. Saldías, attached to revisionism, wrote perhaps the most important work on Juan Manuel de Rosas, originally titled -with the first edition of its three volumes between 1881 and 1887- History of Rozas and his time, and republished as History of the Confederation Argentina. Embarked on this task, he visited Manuelita in London, who kept the file that her father had taken to England, plus the correspondence gathered during her years of exile. Kindly, Máximo Terrero's wife gave him the documents that the historian consulted, which expanded his already rich library. It is said that at his death in 1914 some one hundred thousand ordered documents were kept in the house of Rodríguez Peña 1464 in Buenos Aires, plus the books collected in a lifetime. The vast majority of that treasure passed into the private collection of Juan Ángel Fariní (1867 – 1934), humanist, philanthropist, doctor, historian and book collector.

It could be surprising that shortly after Fariní's death, in 1935, it was due to two great Argentine collectors and bibliophiles, the then national senator Antonio Santamarina and President Agustín P. Justo, the law that ordered the acquisition of that treasure of books and newspapers, to be preserved in the public sphere, in the Library of the University of La Plata. The rest of the Adolfo Saldías – Juan Ángel Fariní collection was acquired from the latter's descendants in 1958 and today forms part of the General Archive of the Nation (AGN). In other words, it is preserved in its entirety in the public sphere.

Among the bibliophiles who dispersed his library during his lifetime, we must mention Enrique Arana (h) (1883 – 1968), historian, teacher and director of the Library of the Faculty of Law and Social Sciences of the UBA between 1931 and 1942. In 1935 the Casa Benito y José Tiscornia auctioned off its book collection with a two-volume catalog raisonné, which featured an introductory text by Guillermo Furlong.

We want to remember Enrique Udaondo's gestures of detachment from him; great collector dared to give his collections to the State for the creation of the museum that today bears his name in the city of Luján. In addition, he donated the historical documents to the General Archive of the Nation.

With regard to the donations received by this institution, between 1933 and 1941 the descendants of Luis Vernet (1791 – 1871), the first Argentine Political and Military Commander in the Malvinas Islands, ceded the documentation until then preserved in the family, of enormous legal value. , historical and sentimental for our country. In the same tenor, it is worth noting the donations made by the heirs of Justo José de Urquiza, Nicolás Avellaneda - his library was sold by the former president to gather resources before his trip to Europe due to health problems; a part of his correspondence was transferred to the AGN by a descendant, Julio A. Roca, José Evaristo Uriburu [13], Victorino de la Plaza, Miguel Juárez Celman and Agustín P. Justo, and the library of Juan Domingo Perón, not very relevant , made up mostly of books received as a gift to the President of the Republic, which were placed in the library of the Casa Rosada, whose main body was transferred to the General Archive of the Nation shortly after the coup that overthrew him, in so much so that another set remained in the dependencies of the Ministry of the Interior. In 1974 its return was proposed, but without any rejection or approval of this initiative -Perón died on July 1 of that year-, the almost 5000 volumes are preserved today in the AGN. Each of these documentary and bibliographical repositories tell us aspects of the life and interests of their owners, all of them Argentine presidents.

The National Academy of Medicine also received an important bibliographic heritage in 1938, when the son of Rafael Herrera Vegas gave them the library formed by his father; some 11,000 volumes and the archive made up of valuable documentation with manuscripts that cover the history of medicine in the Río de la Plata since colonial times.

With a special letter we should highlight the gesture of the descendants of Dr. Pedro Arata (1849 - 1922), whose library of some 40,000 books was ceded in part to the National Academy of Medicine in 1942, and to the Faculty of Agronomy and Veterinary Medicine in 1946. The set brought together incunabula and very unusual works on science, alchemy, agronomy, veterinary science and medicine. The wise Arata had had his house built based on the library with shelves that covered the walls from foot to ceiling, and with sliding stairs.

Another institution that has formed an important library is the Jockey Club of Buenos Aires, started in 1882, whose old headquarters on Florida Street -destroyed by the tragic fire of April 15, 1953 [14]- began to collect books already in the XIX century and in 1921 he baptized that room that housed the printed texts with the name of Carlos Pellegrini Library, its first president. As a result of acquisitions and donations, its heritage has grown notably - its largest collections include the libraries of José A. Marcó del Pont (1851 - 1917), founding member of the Bonaerense Institute of Numismatics and Antiquities in 1872, and the Spanish Emilio Castelar-; over many years it published a quarterly Bulletin where the incessant donations received are recorded.

As expected, public libraries demanded qualified personnel and beyond the attempt made by the National University of Buenos Aires in 1922 with the School of Archivists and Librarians (Faculty of Philosophy and Letters of the University of Buenos Aires) created by Ricardo Rojas , in 1937 Manuel Selva (1890 – 1955) promoted the first professional school of librarians under the orbit of the Argentine Social Museum, with auspicious results. He affirmed then: "The library is no longer a shelf that keeps the water of wisdom, but a source to offer the passer-by the consolation of his thirst". [fifteen]

Twelve years later, Raúl Cortazar presented a new plan at the UBA, which was accepted, assuming the direction of the Librarian Career. Cortazar stood out among the great bibliographers of Argentina, including Manuel Selva himself, Josefa E. Sabor, and among many, Narciso Binayán, Domingo Buonocore, Guillermo Furlong, Jorge Clemente Bohdziewicz, and Abel Rodolfo Goeghegan. All admirable, we want to dedicate a few words to Buonocore (1899 – 1991), lawyer and university professor, for twenty years director of the Library of the Faculty of Law and Social Sciences of the Universidad Nacional del Litoral, where he managed important donations. In Frondizi's time he was appointed director of the Library of Congress of the Nation, Josefa Pepita Sabor accompanied him as deputy director and Susana Santos Gómez was incorporated. The three resigned shortly after taking office because it was impossible to discipline the legislators who took the books by refusing to return them in a timely manner... Buonocore's texts are an open window on the world of books and an unavoidable technical guide for librarians. In the same vein, the pedagogical and professional career of Pepita Sabor stands out; her books and teachings trained numerous librarians in Argentina and the rest of America.

Attentive to this demand for book professionals, from another perspective, in the premises of the College Bookstore -the oldest that had survived in this city-, a school for booksellers was inaugurated with a course that included eleven subjects and demanded a year of study and practices. The Argentine capital continued to be the great Latin American center of contemporary and ancient books, and the training of human resources favored its development.

Active antiquarian bookstores in Buenos Aires offered their catalogues; some organized social gatherings and even had rooms to exhibit works of art. And among the bookstores of modern titles and novelties, we located those that also published. An example of this last modality was Manuel Gleizer, of Russian origin, settled in Villa Crespo since 1918, a Buenos Aires neighborhood chosen by that community. Gleizer was a forerunner in the matter; Attracted by the world of books, he opened his bookstore and, as a good reader, shortly afterwards he launched his own publishing house. He published works by Argentine authors who achieved great recognition, such as Macedonio Fernández, Evaristo Carriego, Eduardo Mallea and Jorge Luis Borges. Decades later, in 1956 Juan Gelman began his literary career with the Gleizer publishing house.

Conversely, the publishing house Peuser S.A. opened its sales premises on Florida Street with two spaces dedicated to the bookstore and the art room. Florida, as we have already mentioned, had become a brand in itself. A few steps from the Peuser Room was the Witcomb Gallery with its section dedicated to old books, and the L'Amateur bookstore. In 1940 Anaconda, by Santiago Glusberg, the publisher, and Casa Ricordi, dedicated to music, were installed. Six years later the Pacific Gallery was inaugurated with the murals of its dome that still seduce us today; Several bookstores worked there: Florida -an annex of L'Amateur-, Rodríguez, Del Temple and Concentra, each one with its specialization, and later, Fausto. Also in 1946 and a hundred meters away, at 681, in the Kraft Room -remember that Adela Calderón de Lahr, a great specialist in old books, directed her section of American Rare Books-, the Friends of the Book Association, chaired by Enrique Larreta, inaugurated the first Exhibition of Incunabula, Manuscripts, Maps and Antique Engravings, accompanied by its catalogue. In said Florida street other art galleries and bookstores were installed; among them, El Ateneo, El Bibliofilo, Atlántida with its books for children and young people, and since 1969, La Ciudad Bookstore, in Galería del Este, which was remembered as a meeting point with Jorge Luis Borges.

By way of synthesis, we warn that any list that brings together the most outstanding antiquarian bookstores in this period must include at least these names: El Bibliofilo -we will talk about this house in the next few pages-; Rafael Palumbo -a patriarch, Roberto Arlt worked in his bookstore and when he wrote The Rabid Toy, he included it among the characters in his novel-; The Faculty, of Juan B. Roldán -Juan Capel, Luis Giglio, E. Matute and the Lacueva brothers were formed there, to whom we will return. Capel was a professional who had his time of glory later in the Librería del Plata; he was also director of the Guarania publishing house, where the first volumes of the monumental history and bibliography of the first River Plate printers made by Father Guillermo Furlong were published; L'Amateur, by Corradini and Mozzarelli, founded in 1926, with its gatherings that brought together unforgettable names, such as Oliverio Girondo, Javier Villafañe, Alejo González Garaño, Bonifacio del Carril, Leónidas Barletta, Manuel Mujica Láinez and Ricardo Molinari. The Cervantes bookstores, by Julio Suárez; the one led by Fernando García Cambeiro, at that time located on Avenida de Mayo 560; the El Ceibo bookstore, by Luis R. Lacueva, and the Fernández Blanco bookstore, opened in 1939 by its founder, Gerardo Fernández Blanco, who was succeeded by Gerardo Fernández Zanotti, an expert antiquarian bookseller who contributed to the prestige of this trade in the country . The book office that, within the Witcomb Gallery, was directed by the German Pablo Keins, who died in 1967, a great antiquarian bookseller, promoter of the Association of Antiquarian Booksellers, also deserves its space in this review. Born in Berlin, Keins, the grandson of the famous Florentine bookseller Leo Olschki, had escaped Nazism and in Buenos Aires was the only book professional with a European university education. We continue this tour citing the Ameghino bookstores, by Saúl Israel Helmann and El Retiro, by Ezequiel de Elía, specialized in gaucho literature, a great connoisseur of 19th-century Argentine books and newspapers, and one of the first professionals linked to the universities of the United States. acquiring works for their libraries. And we incorporate into this review, the Pan-American Bookstore, amazing to think about today, whose owners were David and Raúl Béhar, who arrived from Lebanon. Evidently, Argentina brought together “a melting pot of races”, and the Béhars demonstrated it by publishing around 1947 an exceptional catalog of ancient and modern works, of history and fine arts, with a Prologue signed by Enrique De Gandía, today a bibliographical piece of interest. We also recommend including in the list the little-remembered Arandú, whose partners were Julián Cáceres Freyre and Ricardo Molinari.

The Fernández Blanco bookstore continues its march these days under the direction of Lucio Aquilanti, member and president for several periods of ALADA in the twenty-first century. This house, in times of Gerardo Fernández Zanotti (1917 – 1997) managed to consolidate an important clientele with bibliophiles of the stature of John W. Maguire, Bonifacio del Carril, Horacio Zorraquín Becú, Ernesto Fitte, Alberto Dodero, and numerous researchers and loyal readers. , among them, Eduardo Holmberg, Father Guillermo Furlong, Raúl Scalabrini Ortiz, Arturo Jauretche and many more who gathered there in pleasant gatherings.

By then, Corrientes Avenue - widened since the 1930s - had already incorporated bookstores with contemporary titles and old works into its theater offer. Among many others, the Palumbo store was there. All the regulars of that Buenos Aires at night remember the glory of visiting the bookstores after a show; walk between their tables and in front of the shelves packed with copies to "fish" for some captivating title. There were also large gatherings that continued at dawn at the La Terraza confectionery located on the corner of Corrientes and Paraná.

Among the most important booksellers of this period, we pay special attention to Domingo Viau (1884 – 1964), the son of French parents born in Chascomús, an expert in bibliophile matters, as well as a connoisseur of European art and a good painter. Unforgettable exhibitions were held at the Viau Gallery, including those featuring works by Rodin, Edgard Degas and Henri Toulouse-Lautrec. Here we are going to dwell on his link with the world of the book without ignoring a minimum comment on his personal history. Graduated from the Colegio Nacional Buenos Aires and later, from the Asociación Estímulo de Bellas Artes under the guidance of teachers of the stature of Sívori, Giudice and Della Valle, in 1911 he was selected to travel to Europe with a scholarship from the National Congress; He toured museums, workshops and exhibitions, and lived with numerous artists in Spain, Italy, England, Belgium and France, where Paris captivated him.

Already the owner of extensive training, he first worked as a dealer and organized exhibitions and special sales in the galleries of his friends Witcomb and Naón. Thus he was linked with the great collectors of the time. And in 1925 he formed a partnership with Alejandro Zona, a young French bookseller, to give birth to El Bibliofilo, a book store located at Florida 641 with its sales room and a space for gatherings between writers and "amateurs" friends of home. [16] Barely six months later, he opened an Art Salon and in May 1926 Antonio and Ramón Santamarina, both collectors, joined the firm and provided the necessary financial resources to get the initiative off the ground. The exhibition space was expanded and the editions that continue to seduce lovers of good books began soon.

Busy in the evolution of “The Bibliophile. Antiquarian and Modern Bookstore”, Domingo Viau continued with his regular trips to Europe signing commercial contracts, selecting artists and works, and setting up a bookbinding workshop in Paris.

In 1927 he published his first catalog with two hundred records of ancient and modern books; meticulous bibliographic entries that included editors, printers, illustrators, engravers, methods, format, papers and all other information of interest to a connoisseur. The second catalog of books arrived in 1935, it included titles from the 15th century -incunabula-, in addition to his own luxury editions and even a selection of twenty-eight old books "at creepy prices", as indicated by his biographer Max Velarde. By then the editorial project was on its way. It was twenty years and with different labels -Viau & Zona, Domingo Viau y Cía, El Bibliofilo, and Domingo Viau editor- always under his personal guidance, enriched by the solvency of Ghino Fogli. Among his editorial finds we find Julio Cortázar's first book, Presencia, signed under the pseudonym Julio Denis.

Another house that deserves special attention is the one founded at the end of the 19th century by José Pardo Arangüez, and which was run with great success by Román Francisco Pardo during these years. The premises, located on Calle Sarmiento, already resembled a museum; Jesuit and Creole silverware, colonial and republican furniture, medals and coins, old books and lithographs, manuscripts... and the space for meetings where General José Ignacio Garmendia, Félix Outes, Brigadier José Ignacio Zuloaga, the González Garaño brothers, John Walter Maguire (1906 - 1982), Victoria Ocampo, Ricardo Rojas and Ricardo Güiraldes, Alfonsina Storni, Jorge Luis Borges, Manuel Mujica Láinez, and many other intellectuals, writers and collectors. Rosario Julio Marc was among his great clients; Marc's collection gave rise to the provincial historical museum that bears his name in that city. Let's stop for a moment with J. W. Maguirre, who increased the collections gathered by his father, Eduardo P. Maguire, forming one of the most important collections of the time; He was interested in the iconography of the River Plate, colonial furniture, Creole and Pampa silverware, indigenous and Creole textiles, numismatics - whose collection had been started by a brother who died very young as a victim of a motorcycle accident - and books. In 1962, he donated a set of historical documents referring to Admiral Guillermo Brown; They were destined for the Department of Naval Historical Studies, dependent on the Secretary of the Navy. Its director in those years was the ship's captain (R) Humberto F. Burzio. Susana Maguire, her daughter and only heir, preserves all of those pieces gathered by her ancestors, many of them authentic treasures, which are inaccessible today.

She also formed an important library Norberto Rafael Fresco (1859 – 1928) with an unusual set of prints from the Casa de Ninos Expósitos, the first printing house in Buenos Aires. It was inherited by her son, who privately sold many of those papers to Oscar Carbone, while the rest of the works were acquired by Juan Capel, owner of the Librería del Plata; Capel had bought the famous Cervantes Bookstore, from Julio Suárez.

Another prominent bibliophile of the period was Alberto Dodero, the owner of a shipping company whose headquarters, in the heart of Buenos Aires -Avenida Corrientes corner Reconquista- was a beautiful example of rationalist architecture. Dodero formed one of the most important libraries in the country with the first editions of the travelers who toured South America, the most beautiful and rare iconographic albums on this portion of the planet, and the earliest editions of Argentina and the region. Capel sold him important works that had been part of Fresco's library. At a time of economic distress, Dodero decided to sell his collection in London, at Sotheby & Co; his two catalogs -from 1963 and 1964- are an essential reference source. Many of these works are known to have returned to the country, acquired by local bibliophiles and booksellers. Dodero, for his part, when he managed to stabilize his finances, being a passionate bibliophile, brought together a new group that his heirs decided to disperse years later under the hammer of the Martín Saráchaga auction house, in Buenos Aires.

Old and special books, as we have mentioned, were also sold in auction houses. In 1930, Casa Naón offered the library and map library of Estanislao S. Zeballos (1854 - 1923) at public auction. Scholar Guillermo Palombo tells us that some important books had already been sold privately by the son of the founder of this group. , Talo, and several of them, resold by the bookseller Julio Suárez. For that auction, four catalogs were published indicating that they were part of the Succession of Estanislao S. Zeballos. Cutolo warns that the archive of political and historical documents is preserved in the Luján Museum, “in 320 boxes”.

The library of Matías Errázuriz and its sale at Casa Bullrich. The annotated copy indicates a purchase by Oliverio Girondo: lot 203. (Hilario Library)

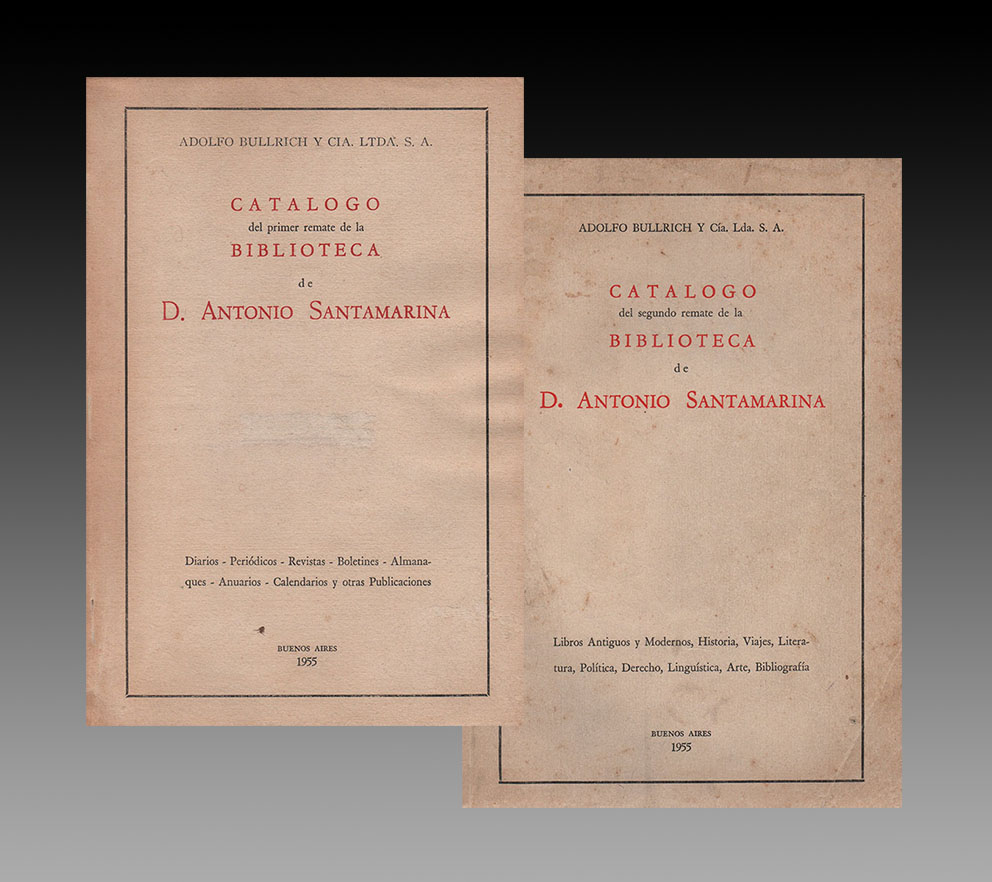

A year later, the library of Clemente L. Fregeiro (1853 – 1923) was auctioned off, together with that of Mitre, the most important collection referring to the history of South America, including books, maps, plans and manuscript documents. In 1942 the Naón house held a special sale with the Matías Errazuriz library. It is very pleasing today to find one of those volumes gathered by Errázuriz, and to identify it in the catalog that Eduardo J. Bullrich (1895 – 1950) wrote with great skill, a great connoisseur of the world of books and an exquisite bibliophile as well, who knew how to gather in its collection a hundred incunabula, manuscripts and prints from the 16th to 18th centuries.

We now return to the history of the library of Agustín P. Justo; Its destiny is linked to the National Library of Lima, so linked to the Argentines since its origin, in 1821. Barely thirty days after the Peruvian Declaration of Independence was signed, General José de San Martín decreed its creation and designated the former Colegio de Caciques, already baptized Colegio de la Libertad, as its headquarters. In the inaugural act, San Martín warned that it was called to be "more powerful than our armies to sustain independence." And in line with this opinion, he donated his personal library that he had started in Cádiz and that he later moved around America making stops in Buenos Aires, Mendoza, Santiago and Valparaíso until finally arriving in Lima. [17]

He was accompanied in this gesture by Monteagudo, García del Río and other individuals. The library soon reached one thousand three hundred volumes and with titles of various interests. That successful origin marked the course of its first decades, until between 1879 and 1884 the so-called War of the Pacific took place with the defeat of the allies Peru and Bolivia. As a result of the conflict, Chile, the winner, appropriated that bibliographic heritage by transferring it to Santiago. The books that remained, it is said, were used for various needs among the soldiers... And more than a hundred years must have passed until, in the 21st century, Chile returned part of that war booty.

In his time and willing to rebuild what was lost, the Peruvian authorities appointed Ricardo Palma -a prestigious intellectual-, who was in charge of such an important mission, "and after directing diverse petitions to all the libraries of the world, to statesmen, to historians , poets and philosophers, managed to fill again the shelves that the winner had emptied with valuable bibliographical contributions from all parts of Europe and America”. [18]

But history played another trick on him on the night of May 9, 1943, when a fire devoured much of that heritage. The most painful thing is knowing that the fire was intentional, it is assumed that it was unleashed to cause the loss of evidence about the robberies that affected the Peruvian institution.

Shortly thereafter, Rubén Vargas Ugarte, the Peruvian scholar and Jesuit priest, like his Argentine peer Guillermo Furlong, traveled to Buenos Aires. Here he made contact with the bookseller Julio Suárez who informed him about the library of the former president of the nation, Agustín P. Justo, recently deceased, and with very good reflexes, Vargas Ugarte contacted the government of his country that immediately motorized a public fundraising campaign, to raise the amount required by the relatives of the bibliophile.

To find out more about those negotiations, we consulted Justo's granddaughter, Mónica, daughter of Liborio, the eldest son of the military man turned politician. “When my grandfather passed away, my father and his sisters had to decide what to do with the library. I know they got great offers mostly from the US but my dad wanted me to stay in Latin America so they finally accepted a much lower offer from Peru after his national library was decimated by fire.' Indeed, this is how the Peruvian investigative journalist David Hidalgo relates it in his book The Phantom Library already cited, where he describes the purchase and stealthy transfer of the more than twenty thousand volumes of "possibly, as an American, the most valuable (private library) in the world." country and in certain aspects more complete than that of General Mitre”, as Suárez affirmed. Closed the agreement with the family - who requested to withdraw a few titles to keep in their possession, those that remained in Argentina -, the library was transferred to the Embassy of Peru in Buenos Aires in an operation led by the Minister Counselor José Jacinto Rada. Inventoried and packed in 330 boxes, except for a few copies that traveled to Lima in a diplomatic bag, the historical books and manuscripts were transferred to the Rimac ship of the Peruvian Navy and without authorization from the Argentine government, as indicated in the detailed account of David Hidalgo, and in September 1945 they arrived in Lima. [19]

Another great library that went abroad was the one formed by Ernesto Quesada (1858 – 1934). There are those who judge that it was the most valuable among the individuals; it gathered more than 60,000 books and 18,000 historical documents and manuscripts. It is preserved in the Ibero-American Institute of Berlin.

We leave for the end of this chapter a review of the Buenos Aires Institute of Numismatics and Antiquities; created in 1872 and short-lived at that time, it restarted its journey in 1934 with the participation of numerous historians and collectors, a host of unforgettable names such as Rómulo Zabala (1883 – 1949), José Marcó del Pont, Enrique de Gandía, Carlos Roberts and Juan Canter, its first board of directors. That year, in the halls of the Association of Friends of Art, the first Argentine numismatic exhibition had been organized with such success that it sparked the idea of refounding the institute. Nine years later, Bulletin number 1 was printed, head of the series of a publication that has spread with an outstanding level of collaborators and articles, being a valuable reference source.

Notes:

1. Bulletin of Argentine Bibliographic Studies, No. 3, April 1997, Buenos Aires, pp. 99 – 100.

2. Today, with museums -one, the Museo Gauchesco and Parque Criollo Ricardo Güiraldes-, artisan workshops, rooms open to visitors and an urban concern to conserve its identity as a people of the Buenos Aires plain closely linked to the countryside, it attracts local and international tourists.

3. Guillermo Palombo: The "Facundo" of Argentine bibliophiles. In Virtual Bulletin Artisan Hands in the art of the people, No. 2, June 2004, Buenos Aires.

4. Its catalog No. 25 is a beacon in bibliographic searches. It reached such significance that the great Spanish bibliographer, Antonio Palau y Dulcet, used it as his reference in Buenos Aires. The work Manual del Librero Hispano-Americano, the famous Palau with its 35 volumes, is the great bibliographical inventory on the scientific and literary production of Spain and Latin America.

5. Marcelo E. Pacheco, Collecting Art in Buenos Aires. 1924 – 1942, Buenos Aires, El Ateneo, 2013, p. 268.

6. Its owner director, Natalio Botana, set out to compete against the cultural supplement of the newspaper La Nación and with a product aimed at readers with fewer resources, he created an exceptional publication. Years later, Borges recalled his experience in that publication: "The true beginning of my career lies in the series of sketches entitled Historia Universal de la Infamia, intended as collaborations in Crítica in 1933 and 1934."

7. The first company of these characteristics was created in 1812, in London, which was followed by the one inaugurated in France in 1820, succeeded by many others in that country, and also in Spain, Chile, Belgium, the United States, Switzerland and Italy.

8. Vicente Ross, Argentine Bibliophiles. Jorge Beristayn, Buenos Aires, Ed. Kunken, 2010. // Bibliophilia: A passion? Buenos Aires, Printed in Artesanías Gráficas SRL, 2001, p. 17.

9. Juan Suriano, Argentina between the two world wars, In “Friends of Art 1924 – 1942”, Buenos Aires, Malba – Costantini Foundation, 2008, p. 70.

10. Years later, renamed the Classical and Contemporary Library; between 1938 and 1982 he edited 478 titles.

11. Carlos Ibarguren himself has told it, in 1905 he discovered in the basement of Manuel Alejandro Aguirre's house a chest full of historical documents linked to the Anchorena family. The commercial documents were donated to the General Archive of the Nation; those that alluded to the foundation of towns and cities were transferred to the Archive of the province of Buenos Aires, and those of a political nature, including the letters exchanged with Juan Manuel de Rosas and other public figures of the 19th century, remained in the hands of his family. until in 1994 they arrived at the Jockey Club Library as a donation from the sons of that historian.

12. María Teresa Giraldes, A bibliophile passion almost as exclusive as politics, in La Prensa, Buenos Aires, Sunday September 6, 1992.

13. In the library of General José F. Uriburu, the personal archive was kept, which, upon his death, the three sons donated to the General Archive of the Nation. Between April 1990 and March 1992, the documentary collection of the former president was classified and prepared for use based on an agreement between the AGN and the Union Study Center for the New Majority.

14. That attack wreaked havoc at the institution's headquarters, where members of Argentine high society met, active representatives of the most conservative interests, the target of criticism from Juan Domingo Perón who raised his voice against the "oligarchy."

15. Manuel Selva, College for Librarians, 1937, p. 109.

16. From its beginnings, that bookstore set out to promote bibliophile by having a space for the library of “eminent bookstore catalogs and manuals”, for the consultation of those initiated in the arts of good books.

17. José Pacífico Otero, San Martín and the library of Lima, Article published in La Nación, August 11, 1935. Transcribed in “San Martín and the books”, National Library of Buenos Aires, 2014, pp. 29 – 33.

18. David Hidalgo, The Ghost Library, Lima, Editorial Planeta. 2018.

19. David Hidalgo, ob. cit. 2018, p. 77-83.