In June 1967, at the Visual Arts Center of the Torcuato Di Tella Institute, the exhibition Surrealism in Argentina took place. Jorge Romero Brest, then director of said Center, summoned Aldo Pellegrini, who was curator of the exhibition and author of the introductory text of the catalog printed for the occasion. As if he had felt that the true nature of this avant-garde was still unknown, in that text Pellegrini once again explains, for example, that surrealism is not an artistic movement but an ideological one, which uses artistic expression as a mechanism of liberation; that surrealism has, at the same time, an affirming side that aspires to a world dominated by freedom, poetry and love, and a denying side, which challenges the hypocrisy of its time; that surrealism does not deny reality, but rather postulates a broader, absolute idea of reality, not only limited to the physical world but also the result of its union with the spiritual world; that surrealism is an art of free imagination, fundamentally unleashed by automatism, a procedure through which it is intended to avoid the action of the critical judgment of reason; that for the surrealists, beauty is not calming but disturbing, and that is why “every surrealist work makes the unsuspecting spectator uncomfortable and uneasy, it tears him from his false security, it breaks his conventional schemes.”

But all these statements, which Pellegrini applies to art, could also be applied to poetry. Less known than the catalog of the Surrealism in Argentina exhibition is the printed Surrealist Location, also published in 1967 by the engraver and illustrator Pompeyo Audivert. There, Audivert discusses the origin of the Argentine surrealist poetry that Pellegrini had established in his text, as well as contesting the selection of works made for the Di Tella exhibition. In his words, it was not Pellegrini with his magazine QUE in 1928 but he himself “who in 1924 published the first folder with surrealist engravings published in the country. Its title is Six engravings, made in linoleum on themes by Fijman. With the sale of this folder, Fijman's book Molino rojo was later published [...] in 1926. It can safely be considered the first book by a surrealist poet published in the Argentine Republic.»

The word location, with which Audivert titles his print, only highlights the problem of ascription, which he claims for himself. Where is Argentine surrealism located? When did it start (and how many times) and where did it go? Who were its “true” representatives?

The truth is that, after the publication of Molino rojo in 1926 or the appearance of QUE in 1928, two decades passed—until the release of the magazine Ciclo in 1948—in which the drifts of surrealism in Argentina are not easy to understand. identify. Even so, in those years you can find, scattered in different magazines and newspapers, news about European surrealism and evaluations of its exponents who shaped a space for the reception of this avant-garde in the country and made possible the emergence and consolidation of a surrealist group. Argentina in the decades of the fifties and sixties.

By 1924, while André Breton published his first surrealist manifesto in France, the cultural and intellectual field of Buenos Aires was agitated by the effervescence of different groups of young people who, echoing the modernizing boom of the time, promoted a process of radical renewal. This phenomenon, which permeated the publications, literary magazines and editorials of the time, was nourished by the novelties coming from Europe, mainly from Paris, the intellectual metropolis par excellence in those years. From there came the echoes of Cubism, Futurism, Dadaism and, later, Surrealism, which were given a different reception.

QUE (WHAT). Number 2. 1930.

At the end of the 1920s, a group of young medical students, led by Aldo Pellegrini, expressly read the French surrealists and early tested an Argentine surrealist program, expressed mainly in the two issues of the magazine QUE (1928 and 1930). However, the publication had no impact. The thing is that in the 1920s and 1930s the local cultural field offered some resistance to the expressions and reflections of this avant-garde, and presented difficulties in identifying what was novel and revolutionary in it. However, the periodical publications that gave it a place in those years - articles that appeared in the magazines Proa, Martín Fierro, Sur, in those of the Catalan community in Buenos Aires such as Catalunya or Síntesis and even in others that came from Spain but had great circulation in the Buenos Aires circuits, such as La Gaceta Literaria and Gaceta de Arte—were generating conditions of listening and readability so that an Argentine expression of surrealism could compete for a place and consolidate itself in the decades of the fifties and sixties. While the second post-war period fractured French surrealism, confronting its leaders, and critics predicted its exhaustion, the time arrived for its projection in America.

The institutionalization of psychoanalysis in the country (the basis of many surrealist ideas) also contributed to this process. Enrique Pichon-Rivière, one of the introducers of Freudian theories and founder of the Argentine Psychoanalytic Association in 1942, appears in this instance as a renewing factor with respect to that first experience of the magazine QUE, leading a new impulse to the surrealist movement promoted by the Ciclo magazine, of which he was director along with Aldo Pellegrini and Elías Piterbarg. Published in two issues (November-December 1948 and March-April 1949), Ciclo proposed a renewal of surrealism that, after twenty years, was bursting onto the local scene again.

In parallel to his participation as co-director of this magazine, Pellegrini founded, together with David Sussman, a former member of QUE, the Argonauta publishing house, a fundamental project for the promotion and development of surrealism in Argentina. There he published his first book of poems, The Secret Wall (1949), which surpassed the proposal inaugurated by QUE: in addition to the reflective and collective work of the magazine, his individual literary praxis now appeared, of a surrealist nature. Pellegrini would once again be in charge of maintaining a line consistent with the doctrine and leading the core of poets who followed him in subsequent publications.

Soon came A Starting from Zero, directed by Enrique Molina. Published in two stages (two issues in 1952 and one in 1956), it was the magazine that best represented the Argentine surrealist spirit and in which a group of poets with a certain organicity ended up being formed. Prior to the last issue of A Partir de Cero, Letra y Línea (1953-1954) appeared, also directed by Pellegrini and financed by Oliverio Girondo. This publication opened the game to a number of actors of diverse origins, always channeled around avant-garde ideas: those who had been acting within surrealism were joined by writers, plastic artists and other figures who came from other schools and thoughts, like inventionism. Towards the end of the decade, one of the youngest members of the group, Julio Llinás, anointed with a revisionist desire for the movement, founded and directed Boa (1958-1960), in which the group no longer operated as such, although some of its members collaborated in it.

Starting in the sixties, the surrealist core came into contact with a group of young people who, identifying with this avant-garde, demanded from Argentine surrealism a political position that had not occurred until now. The figure of Vicente Zito Lema was central to this new generation. He was in charge of the magazine Cero (1964-1967), in which the synthesis between surrealism and politics was evident. Other projects followed, where some members of the group still came together: La Rueda (1967) and Talismán (1969). This last magazine, also directed by Zito Lema, dedicated its first issue to the poet Jacobo Fijman, linking him to Artaud and recognizing him as one of the precursors of surrealism in the country.

The seventies, however, would close a cycle for Argentine surrealism. In just a few years, the death of some of its leaders coincided (that of Aldo Pellegrini in 1973, Carlos Latorre in 1980, Juan José Ceselli in 1982), the outbreak of the civic-military dictatorship in 1976 and the horrors of State terrorism, which impacted directly on the younger generation: Miguel Ángel Bustos, a PRT activist, was kidnapped in 1976 (he remained missing until his remains were found in 2014), and Vicente Zito Lema, lawyer for political prisoners and member of the ERP-22 of August, he had to go into exile in 1977.

Retracing from the present the trajectory of surrealism in Argentina (its beginnings, its production, its withdrawals and successive resurgences) allows us not only to see panoramicly its history and that of the group that promoted it but also to recover the aesthetic and ideological characteristics of this avant-garde. The National Library has in its collection, and makes available to the public on this occasion, the books and magazines in which these artists created particular variations of the surreal vision, as well as the local periodical publications in which the news of the European surrealism.

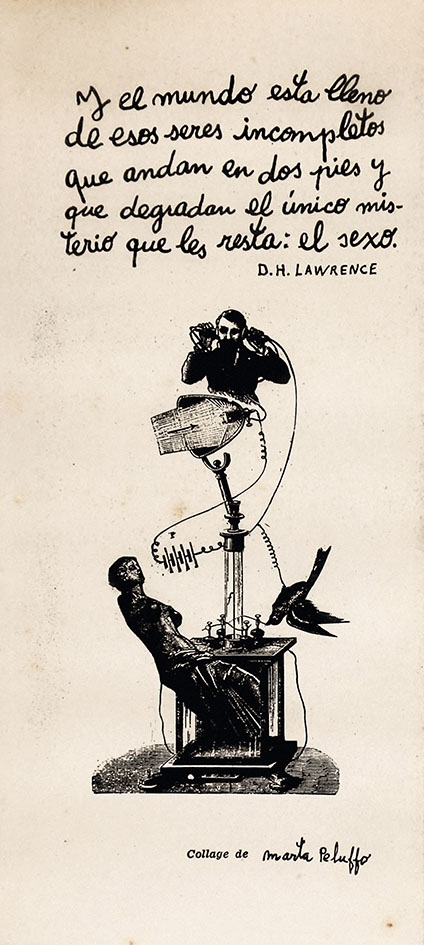

Juan Andralis. Untitled, s. a. Ink on paper.

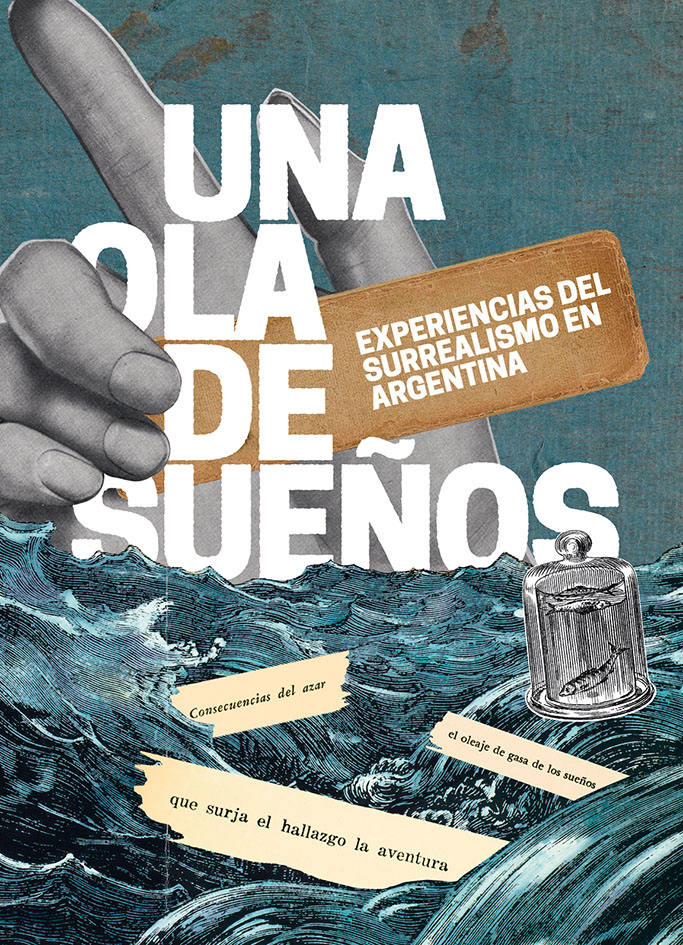

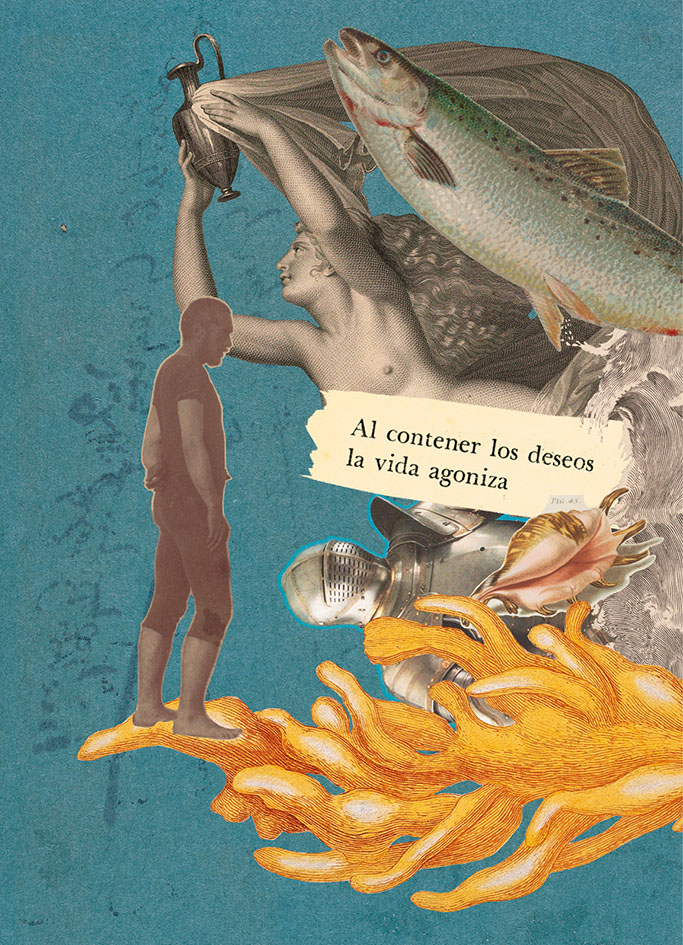

Enriched thanks to the contribution of archives and private collections, the exhibition A Wave of Dreams. Experiences of surrealism in Argentina proposes a tour that reconstructs the local chapter of this avant-garde, recovering in its title one of the inaugural manifestos of French surrealism and evoking its projection towards this shore. Along with the bibliohemerographic materials already mentioned, drawings by Juan Batlle Planas, Juan Andralis and Miguel Ángel Bustos are also exhibited, some of which had never before been exhibited to the public, and a series of letters, personal documents and drawings inside the books. that shed light on the reflective and programmatic threads that wove the link between the main references of the Argentine surrealist group.

A wave of dreams. Experiences of surrealism in Argentina can be visited until March 31, 2024 from Monday to Friday from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. and Saturdays and Sundays from 12 to 7 p.m. in the Juan L. Ortiz room of the National Library. Free entry.

* Special for Hilario. Arts Letters Trades. Adapted from the curatorial text of the catalogue.