In August of this year I was invited to give a conference in Bahia (Brazil) within the framework of a Colloquium on Heritage, Culture and Memory organized by the Federal University of Bahia. Likewise, during said meeting, the book “The Latin American votive offerings, Brazil, Mexico and Argentina” was presented, with texts by José Claudio Alves de Oliveira addressing the first two countries and mine, in reference to the natives of Argentina.

For the conference I proposed as a topic the Survey of National Heritage, movable property, which we carried out with my wife, Iris Gori for 19 years and that we did as researchers at the National Academy of Fine Arts. To do this, I reviewed, after many years, the books that we made for this Institution. It is legal to clarify that the minimum team, two people, was contrasted with those made up of ten and up to twenty people who did the same work in other countries such as Brazil, Mexico or France.

The last of these books, “Santa Catalina de Córdoba”, was published with the help of the Getty Foundation in 2000, while the first of them, “Provincia de Corrientes”, was published in 1992, 31 years ago. . The academics Héctor Schenone and Adolfo Ribera directed the project, and, in my case, I was also the photographer of the entire undertaking.

With the books in sight and in order to summarize the work in some way, the first thing I did was add up the amount of heritage assets documented in the various provinces where we did the survey: Corrientes, Entre Ríos, Jujuy, Salta and Córdoba .

The sum obtained was 3,500 published pieces, and let us keep in mind that 25% of what was documented was discarded due to lack of interest in the material or other reasons. That discard was recorded and registered in the Academy.

The official publications of the ANBA correspond to Corrientes, Jujuy, Salta and Córdoba. We made other books and folders independently whose titles are: “Saint Teresa of Jesus, Divine and Human together” (1993), “Jesuit Sacred Enterprises” (2003), “The monument to Sarmiento made by Rodin” (2004), “ The Order of Santo Domingo in Córdoba, history and heritage” (2004).

In addition, there were interesting and attractive derivations of said survey such as, for example, the one carried out in 1980, in the 19th century church of the town of Itatí (province of Corrientes), which is next to the new Basilica, the Museum of the Virgin with a magnificent set of works of imagery and furniture, which are published in the book corresponding to that province. I completely renovated this Museum in 2005.

The ANBA survey of movable property was the most exhaustive and prolonged that was carried out in the country. Years before, the Institution had published the famous and mythical “Notebooks” with another criterion and perspective.

The work excluded archeology and architecture and art produced after about 1930. The goal was to know, as accurately as possible, how much and what had been done previously and was preserved in the country.

This was achieved through the work method. We settled in each province for a year or more with the purpose of visiting it in its entirety and seeing what was in cities, towns, places, private houses, ranches, churches, cathedrals, chapels, museums, mayor's offices, etc.

This was a “reasoned survey”, that is, a sum of objects was not made with a quantitative criterion, but rather a technical sheet and general plan photos and details were prepared for each one of them and they were related to other similar goods. that were appearing in that or other provinces.

Thanks to this slow method, which consisted, especially in churches, of downloading all the images and paintings from the altarpieces, cleaning them and analyzing them, we discovered painters, silversmiths, and sculptors who were incorporated into the Art History of the country.

In a brief summary we will list only some findings.

Province of Corrientes

In Itatí, in the church where the Museum now operates, at the beginning of the 20th century and following the fashion of the time, it was decided to replace the old and “old” altarpiece from the 18th century with a neo-Gothic one. But the height of the Virgin, which would be located in the central niche, was not measured. When they wanted to put her in it, they realized that there was no room for it and they resorted to the easiest solution: he cut it below her feet to leave her without a base. It is now 126 cm tall! And her notable disproportion is hidden with a long tunic and mantle. The original face of the image was dark-skinned, that is, similar to that of the inhabitants of the place, with successive and documented retouches made in 1853 and 1885, it was clarified.

There are important Jesuit carvings in the capital city and in Saladas, San Miguel, Loreto [from the Jesuit Reductions of Yapeyú], Santo Tomé, San Carlos and La Cruz.

It is true that, thanks to the working method (which consisted of touring the entire province) we found and documented a quantity of popular imagery that was in the hands of individuals and that was not known, where San Baltazar stands out, whose cult was brought by the blacks Brazilians after the War of the Triple Alliance.

Also relevant is the painted votive offering from the 19th century, which is in the museum we built in Itatí, where the Virgin of Itatí is seen, in the 18th century altarpiece as it was before said piece of furniture was renovated. During a restoration carried out by Alicia Beltramino in 2005, the text appeared: "Virgin of Itatí, patron saint of Tuyutí, painted by Juan Bedoya, in 1872."

There is magnificent furniture on display in the museum, which was made in workshops established in the 18th century in Itatí. A chest of drawers-desk is dated: 1768. The confessionals and seats are from the same period.

Province of Salta

The images that were made in this Argentine region, both in the 18th and 19th centuries, are not those produced further north, such as in Alto Perú and in Peru itself. Image makers of European origin did not arrive here.

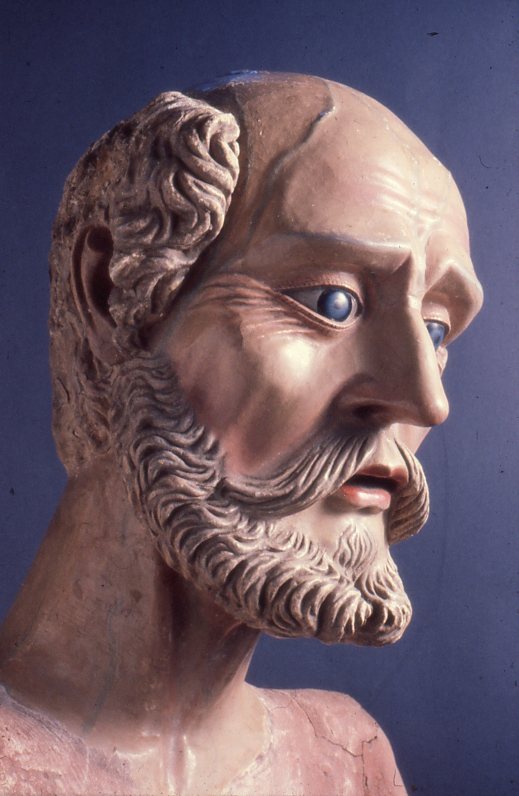

In the northwest of the country, a more basic, schematic imagery is made, and paste masks applied to a core of cardón are used to make them. The hair and beard are made with modeling clay and the glued fabric is placed on the wooden candlestick that completes the figure. They are very expressive figures with character.

The Virgin of the Miracle is a magnificent wood carving, 105 cm high, which has joints in the elbows and wrists, showing that it was made to be worn. When we undressed her, we could see, painted on her chest, a sign that reads: «She was embodied by Tomás Cabrera. Year 1795». (See photography)

This painter and sculptor, of whom there is little news; probably born in 1748, he died in 1801. His most famous work is preserved in the National Historical Museum, the painting titled “The meeting of Cacique Paiquín with Governor Matorras” that he dated in 1774 [1]. He was named Senior Master of Painting in 1789, as recorded in the Chapter Acts of Salta.

The Lord of the Miracle has a legend that says that he appeared floating in the port of Callao inside a box. The Christ measures 190 cm high, is highly repainted and has glued fabric purity cloth.

We have already talked about Felipe de Rivera, a notable sculptor, in an article for this same space (link: https://hilariobooks.com/blog-article.php?slug_es=la-presencia-del-escultor-felipe-de-rivera -in-salta-santiago-del-estero-and-cordoba-argentina-in-the-18th century) there is a head of the same saint in the church of San Francisco, another in Santiago del Estero in 1762 and during this survey, We find in the church of Santo Domingo, in Córdoba, another Saint Francis made and signed on the back of the neck with its date: 1794. The three sculptures have the same anatomical treatment that characterizes them.

Province of Jujuy

Here we made a discovery of great relevance; It was in 1986 and meant incorporating the name of Mateo Pizarro into the History of Art of Argentina, an excellent artist who acted in the Puna of Jujuy in the last decades of the 17th century and the first decades of the 18th century. He had been born in Bolivian lands that by then were the same soil. We discovered the signature in the painting “San Ignacio de Loyola” that is in the church of Uquía. It is based on an engraving by Schelle Adams Boswert from 1659, on a cartoon by Rubens. He holds the book of the Constitutions and on the left page appears a Christ Child in grisaille with the orb crowned by a cross. (See photograph) Pizarro's works show wisdom in the treatment of drawing and color. He has a deft hand that differentiates materials such as fabrics and metals. He worked for Juan Campero y Herrera who had him bring from Europe the “Smalte” (vitrified cobalt pigment), carmine and malachite, all products that were found in his paintings during laboratory tests.

In the province of Jujuy we also document works by Diego de Aliaga, Marcos Zapata and Melchor Pérez de Holguín.

Almost all of them had been painted on burlap and other types of fabrics where products from Europe were wrapped. They show several seams to form the necessary size and in many there are customs “marches” where the place of destination is recorded (for example, Cartagena) and the weight of what they were carrying.

Province of Cordoba

The image of the Virgin of the Miracle is the one that shares the legend of the Christ of the Miracle of Salta, which says that two boxes appeared floating in the port of Callao in the year 1592. Both with labels indicating where the images they contained should go.

Little and nothing was known about her. With the authorization of the Dominican fathers we were able to undress her and see how a modern, pink fabric covered the entire piece from the waist to the base. Her head had been shaved off, removing part of her hair and the veil that covered it. The authentic hands had been cut off at the height of the fists, preserving the edge of the dress of the original hands.

With the permission of the priests, we made a 10 x 10 cm window on the back of the glued fabric with the intention of verifying whether there were remains of the original carving. And so it turned out, there were obvious remains of the carving and the stew as it arrived from Spain in the 16th century. They allowed us to remove all the new fabric, revealing the wooden slats that made up the flare of the garments. (See photograph) All the polychrome and gold were splashed with the chalk and glue with which the fabric had been hardened. The arms had been cut and arranged so that they could hold the Child God that the original image did not have. The custom of roughing up images to be able to dress them and thus decorate and enrich them with clothing and jewelry is a Spanish custom from the 18th century. New ears were made so they could be fitted with earrings. We found a paper folded in four and held with a thumbtack over the original carving. It was dated in the year 1917 and in which it was clarified that the community of that year had resolved: «Given the lamentable state of the image, for having it, the ancestors, having cut it to dress it, it seemed appropriate and reverent to place a dress on it. Her waist was thinned in order to dress her and the ribbons were added to make her more stable, which is what she is wearing now", and that text continues, "that the image has been full size and apparently very beautiful, ignorance and piety they made the mistake of breaking it into pieces to clothe it.

Another discovery was the signature of the author of the magnificent carving of the "Transverberation of Saint Teresa" that is on the main altar of the convent of the Carmelite nuns. It is made of carved and polychrome wood, 295 cm high and Alfonso Bergaz (1744-1812) was its author.

Also in the Jesuit Museum of Jesús María we find a Nazarene, dressed, full-length and standing, with shell eyes and mother-of-pearl teeth, who has painted on his chest "Ilario Cabrera made me in Salta" and on his back "Lo Rosendo de Frías had it made. 1801».

A job that took us several months and that meant assembling a scaffolding with wheels with which we walked the entire perimeter of the church of the Company of Jesus, in the center of the city of Córdoba, at 10 meters high, allowed us to document, for the first time, the 50 sacred companies, carved and painted, measuring 85 cm high by 70 cm wide. (See the detail of one of them in the photograph)

The set of these carvings expresses the thoughts and teachings of the Company to its disciples. They alternate with paintings that show members of the Company, such as Saint Domingo de Guzmán, Saint Augustine of Hippo and Saint Peter Claver, among others.

Finally, I want to refer to the discovery of mural painting from the 17th and 18th centuries, in the old and unused refectory of the convent of San Francisco, in the center of the city of Córdoba. The mural was covered by a huge painting that we took down in 1989 to document and restore. Under it was the cartouche preserved without the successive layers of lime with which the entire refectory had been painted at different times. The entire room had mural paintings that were discovered as the restoration plans progressed under the direction of the Mexican Rodolfo Vallín. The themes are varied: vases, fruit bowls, garlands, a baseboard that imitates tiles, etc. The cartouche that was covered by the oil painting that we removed, has a scallop and a blue and green frame as its crown. Inside it it reads: "Noble Saint Francis, may your fame sound loud on a loudspeaker; for such a humiliated seraphim you are marked by God himself." (View fotography)

This research has saved a lot of work, has generated awareness and, from the creation of the TAREA foundation (in a fruitful alliance of efforts between the National Academy of Fine Arts and the Antorchas Foundation), it was achieved, over ten years restore and conserve a significant amount of paintings from all over the country. We must also point out that, as a consequence of our detailed working method, it was possible to incorporate artists who were previously unknown into the country's art history.

But we believe, as I wrote in the introduction to the book of Santa Catalina (2000), that perhaps the conclusion that can be most useful to us is the one that removes part of the inferiority complex for not having a heritage comparable to that of other countries in America.

Without a naive spirit or a misplaced nationalism, and without the intention of creating a false image of what was produced, of what there was and is in the country, we can affirm, and with examples, that Argentina has an outstanding heritage artistic that deserves to continue being documented, studied and preserved.

Note:

1. Marta Penhos, Ver, conocer, dominar. Imágenes de Sudamérica a fines del siglo XVIII, Buenos Aires, Siglo veinte editores, 2005.

* Special for Hilario. Arts Letters Trades