End of September 2023. A sunny Sunday, ideal to visit, before leaving Italy, the exhibition on the courtly table that had just opened in the Venaria Reale, one of the residences of the House of Savoy. First in line behind a briskly climbed staircase, three words in Italian on the door of a small room to the right of my destination diverted me from the planned schedule: “Poesia della Materia.” An exhibition by the Turin artist Ezio Gribaudo, whose name I did not know until then. To my surprise, a geological history of the world was framed in those rooms of the palace. Footprints, paper fossils, engraved letters, meanders, altimetry and bleach targets. Imprints and impressions resulting from the work of men and years. An artistic creation where logogriffs [1], that reality, event or behavior that cannot be understood, or that can hardly be understood or interpreted, are transformed into topographic strata of blotting paper, the material par excellence of philatelists, those travelers. that traveled the world through the names and landscapes of the stamps. Where the news sinks into the paper. Where fleeting is gold.

Panoramic view of the Venaria Reale. Photography: Courtesy www.italia.it

Before leaving, I couldn't avoid buying the catalog knowing that the suitcases, at that point, couldn't tolerate one more gram. A book that I devoured that same night to find out that Gribaudo had died the previous year and that this exhibition had opened on June 22, the first anniversary of his death.

There, in the catalog, I saw the images of his studio, a work by the architect Andrea Bruno, the same one of the Castello di Rivoli museum and the renovation of the Regional Museum of Natural History of Turin that I had also visited in those last days. . Reinforced concrete cubes, a kind of bunker, a stripped geometry marked by the impression of the formwork, one of my father's crazy things. Impossible to resist that combination of things that marked the childhood of the daughter of an engineer from Quilmes, a lover of structures and lines without too many twists and turns. And that's where I headed.

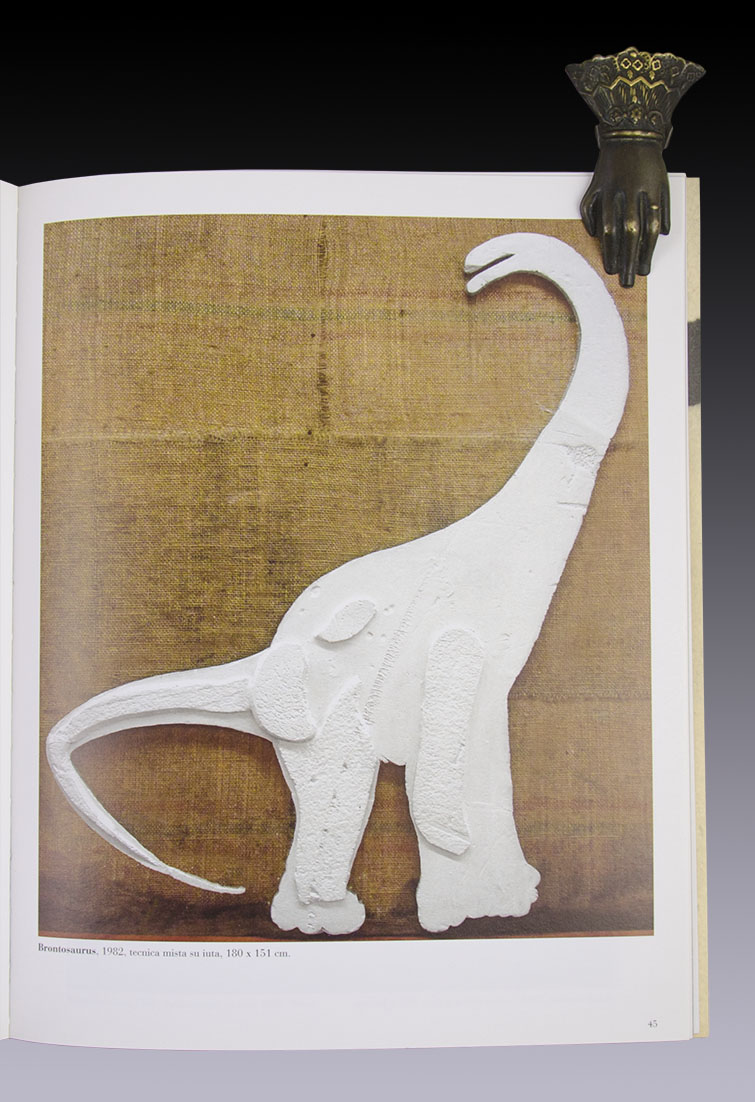

I don't remember how I found the address, but the studio is on the other side of the Po River, past the Church of the Great Mother of God, at the foot of the Turin hill and at the end of a street, barely visible. At the door, second surprise, maybe it was the third, I don't know: a small garden, full of dinosaurs presided over by one in stone that, with its long neck like a diplodocus, seemed to be born from the walls of that house dated 1974.

About to return to the agenda with everything pending from that, my penultimate day in the city, I saw a man leaving the studio with some rolls destined for the paper containers. Those who have read me in these pages know of my weakness for garbage and probably some of you remember my thesis that proposes that prehistoric archeology and paleontology emerged from the garbage dump and from that interest in giving scientific and economic value to the waste of humanity and the past of the planet. So, without effort, you will also conclude that my luggage added a few kilos again.

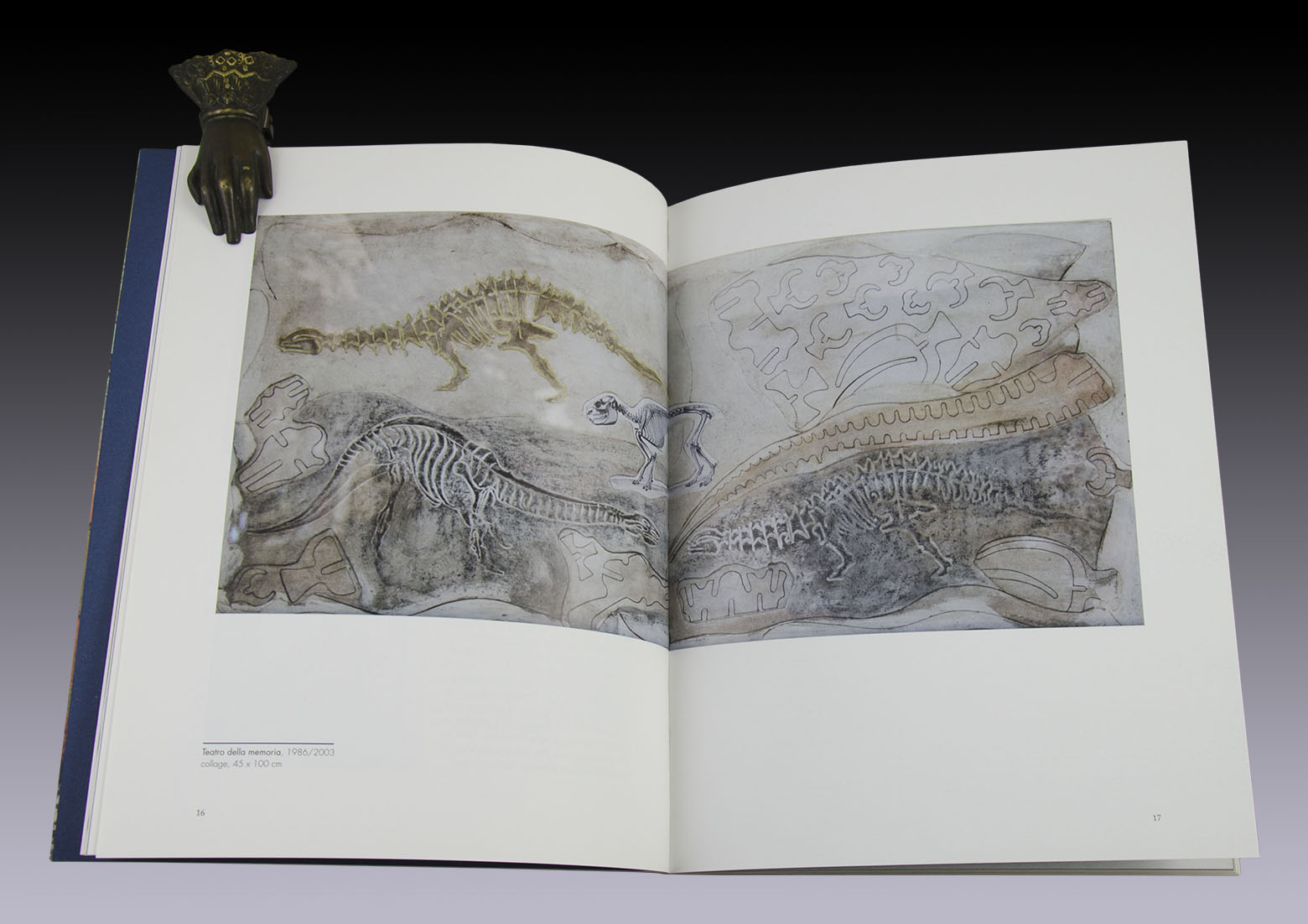

Nor could I avoid talking with the said man who invited me to come in and talk to Paola Gribaudo, Ezio's daughter, who, that morning, was in the study. The surprises no longer had order or number: suddenly I found myself surrounded by dinosaurs, on paper, in tempera, in watercolor, on jute, in white on white, in cages, flying, crawling along that staircase and in the light of those open windows. the Antonelliana mole.

I soon learned that Gribaudo's interest in dinosaurs began in Oceania, that kind of lost world, where the strangest plants, animals and rocks coexist with the present that, as we know, is dismantled at every moment. But, above all and as it could not be otherwise, it was consolidated in a natural history museum, in its case in New York, where the bones of those animals that no human has been able to see next to it, became a skeleton. thanks to the industry and wealth of the tycoons of the United States. How can we not be enthusiastic about that past mounted and supported with metal, with those works that are too human, too contemporary but that aim to bear witness to what happened hundreds of millions of years ago? How can we not admire the feat of representing themselves as the image and likeness of a nature that never was and that only exists thanks to us, its inventors? A us and a gadget that includes museums, paleontologists, artists, filmmakers: all those human beings who take a nap hugging a dinosaur and wake up ready to give it color, shape, filling. Perhaps that is why some of Gribaudo's dinosaurs resemble the animals of European Paleolithic art; After all, humanity has never stopped living with them.

Because at this point, dinosaurs, the real ones, have never left the earth; They come from toy boxes, from paper, from drawing; They are projects, works, sculptures, whose authorship, however, dissolves in the anonymity of natural history. A random combination of bones and plaster, resins and silicones, articulated by iron that replaces tissues swallowed by time. A structure that - whether in museums or in the anatomy that supports us - begins with the spinal column, from which the ribs, the head, the waists, the legs hang. Not for nothing, Gribaudo, who, after all, comes from the art of printing, knew how to create a graphic type with the pieces of wood with which the dinosaur models are made to be assembled: an inverted U or tuning fork that repeats itself in many of his works, like a type of Jurassic printing press.

But, as Gribaudo also suggests, dinosaurs coexist with us. Or, put another way, the 20th century cannot be conceived without its existence. United States, the country with the highest number of cars per family; Turin, the city of contemporary art, the former capital of the automobile. Every car, every kilometer traveled in its bowels, lives and moves thanks to oil and its derivatives. And although this hydrocarbon of fossil origin is, in reality, the fruit of the transformation of organic matter from zooplankton and algae that, deposited in large quantities, were later buried under heavy layers of sediments, who does not remember the explanations that showed how the decomposed corpse of a dinosaur of enormous proportions was transformed into a black and oily stratum that slept waiting for the drilling that would take it to the surface to, thus, improve our lives?

An exaggerated or rather false, but effective, association arising from the press campaigns of an American oil company, the Sinclair Oil and Refining Corporation, a company founded in 1916, whose advertisers in the 1930s used dinosaurs to promote their refined lubricants. from crude oil, which at that time was dated as an event that occurred when they roamed the Earth. The campaign included a dozen dinosaurs, but it was “Dino”, the brontosaurus, a long-necked giant, similar to the one that greets today at the door of Ezio Gribaudo's Turin studio, that captivated Americans and that the company registered as corporate image in 1932. A “life-sized” Dino appeared in 1933 at the Chicago World’s Fair, “The Century of Progress,” along with other dinosaurs built by P. G. Alen, known for his paper mache animals used in movies. Shortly after, Sinclair published an album of figurines and, every week, gas stations distributed images of the dinosaurs to complete it, a campaign that, replicated on the radio, was a huge success.

The album of figurines published by Sinclair in 1935. Collectible since then.

In 1963, a giant green Dino-shaped balloon paraded in the Thanksgiving parade at Macy's, the department store that advertised itself as “the largest store in the world,” and soon became a favorite mascot of customers. American consumers, to the point that, in 1975, he was named an Honorary Member of the Museum of Natural History.

Previously, Dino the brontosaurus had appeared in New York along with eight others that included a plate-covered stegosaurus and a tyrannosaurus; all made of fiberglass and provided with movement and animation. They were destined for “Dinoland,” the Sinclair oil company's pavilion at the 1964-1965 New York World's Fair, where they arrived by barge, waving from the Hudson River. The construction of these beasts had taken three years and was the result of the work of a team of paleontologists, engineers and robotics experts: designed by Louis Paul Jonas, a sculptor of wild animals, they were based on the work of paleontologists Barnum Brown, from the Museum of Natural History and John H. Ostrom, from the Peabody Museum at Yale University.

Dinoland also had machines that, for 25 cents, instantly molded a dinosaur in Dinofin plastic, another product patented by Sinclair. Once the Fair was over, the dinosaurs were disassembled to tour the country and reappear in the 1966 Thanksgiving Day parade, two years before Gribaudo's first visit to New York, when he arrived accompanying his friend Lucio Fontana [2]. which organized its first exhibition on this side of the North Atlantic, the engine of consumer society, where dinosaurs flew even without wings and for a quarter of a dollar, anyone was convinced they could buy their own dinosaur.

Those associations that arose from the hands of oil companies, museums and advertising, gave shape to those desires and to these resin and paper animals, whose history no one remembers anymore but that Gribaudo and Fontana not only saw their birth: they witnessed how, Through the gasoline tank and the stores with the most absurd objects, they settled in the houses of that country and there is no one to remove them.

Today dinosaurs sneak through windows and cracks and today, like yesterday, they tell us about a world where the past and the future are confused according to the convulsions of the Earth and of men. Gribaudo knew how to see it and transformed them into the fossils of the 20th century.

Maybe in a few years, that man who allowed me to enter the studio will wonder why he did it. It will be, that is my wish, when Gribaudo's dinosaurs have left the bunker of his creator to repopulate the planet that - who doubts it - is still theirs.

Editor's Notes:

1. Logogrifos: According to the Royal Spanish Academy of Language, a pastime that consists of guessing a certain word and other shorter ones, which are obtained by combining the letters that make up the first, based on clues about its meaning.

2. Other surprises when learning about Gribaudo's biography, he turned out to be a friend of the Italian-Argentine artist Lucio Fontana (Rosario, Argentina, 1899 – Comabbio, Italy, 1968), famous for his perforated and cut canvases, and for his manifestos focused on the called spatialism. In addition, Gribaudo exhibited his work at the Recoleta Cultural Center in 1998, the exhibition was accompanied by the Catalog.

* Special for Hilario. Arts Letters Trades