The first authorization granted to send books to the Río de la Plata was signed in 1534 and the Franciscan religious were its beneficiaries. These works carried the mission of catechizing the native populations, which is why books of romance or imagination -the popular chivalric novels- were prohibited, since it was feared that the indigenous would read those pernicious texts, so far from the path of God, and " learn vices and bad habits. The royal certificates and even more, the measures dictated by the agents of the Holy Office -the Inquisition had very demanding courts- provoked the censorship of the prohibited titles, although some authors maintain, there were always loopholes through which they traveled to Latin America.

Around the same time, Carlos V had approved Bishop Zumárraga's request to set up a printing press and a paper mill in Mexico City. Without the end of the 1530s, the first printed sheets came to light in the American continent, where little by little other printers arrived and one of them, Antonio Ricardo, after two years of publishing works in Mexico, decided move to Lima. There he received the royal license and with the workshop set up within the Colegio de la Compañía de Jesús, he began his march with a Pragmatica printed in 1584. In his hands the printing press had been born in South America and similar to what happened in the capital of the viceroyalty of New Spain, in Lima, head of the Viceroyalty of Peru, other printers were installed that distributed their works throughout its territory. Books for civil, administrative and religious use came out of those presses; original works -written in the new Hispanic domains, such as Pedro de Oña's Arauco Domado, which Antonio Ricardo published in Lima in 1596--, reissues of titles already published in Spain or Mexico, and bilingual pious works. The Spanish policy of secrecy of the Habsburgs exercised its controls on the works to be published on or from America -they had to obtain a printing license, which was granted as long as they passed the censorship of the jurisdictional court-, and these, once authorized, circulated for the American territory; A good example of this are the books that constantly traveled between Mexico and the Philippine Islands through the Manila Galleon. Similarly, the texts in native languages published in Lima were immediately distributed to the places where these languages were spoken, as happened with the work of Febres "Arte de la lengua general del Reyno de Chile" (Lima, 1765).

With an increasingly developed industry in Europe itself, the circulation of books, aside from shipments to religious orders, spread rapidly. It is known that, in 1607, a merchant in Buenos Aires put 293 volumes up for sale and offered them to a colleague in Santiago del Estero. At that time, let's imagine the delays in communications, having no news about the first beneficiary for sale, he put them in the hands of another merchant, this time in the young village located on the banks of the Plata; here they will have found his new destiny.

The titles arrived in Buenos Aires in the warehouses of the ships dispatched in Spain; For example, in 1637 a Jesuit arrived in our port with a variety of much-needed items; from iron bars to a number of books for the schools of the Society of Jesus, and for various people "who had given various sums for this purpose." In their schools, the Jesuits sold books to individuals -there is a list of these books in the General Archive of the Nation-, they did it at cost price, because they were clear that the circulation of the printed letter was the circulation of culture and knowledge. So much so that some titles imported 17, 20 and even 36 copies; understand, of the same title. True best-seller of the time. And they imported them from Spain, France, Italy, Germany, Flanders. They imported books and maps; Furlong mentions a declaration before the Customs of 12 maps of Paraguay, and a set of books, among them "Politica Indiana", by Solorzano Pereyra.

Another Argentine researcher, José Torres Revello, located in the Archivo de Indias fourteen lists of books that were shipped to Buenos Aires between 1698 and 1728 for sale there. If there was even some ecclesiastical authority that complained about the excessive number of books that circulated in these lands. We expressed it at the beginning, the Church tried to control all the titles that were sent - a task of the Court of the Inquisition -, and the royal authorities did the same.

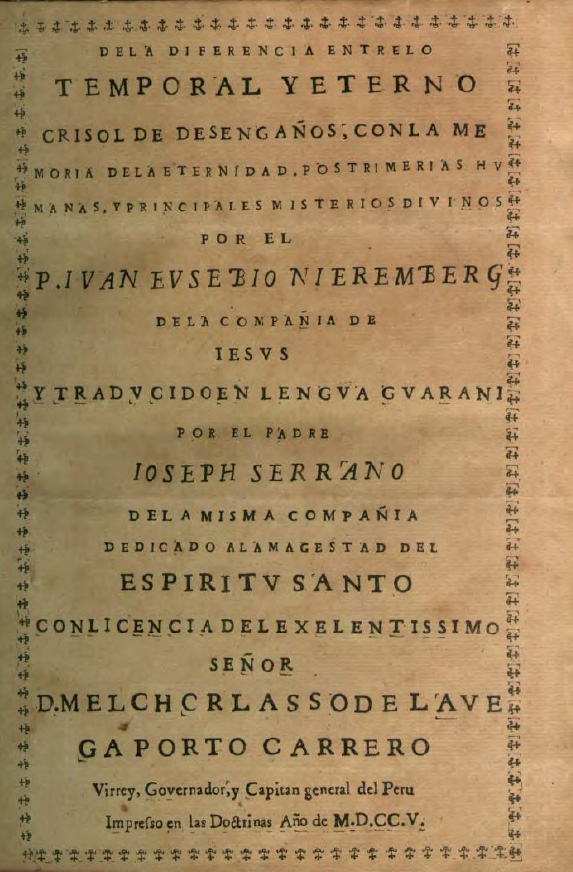

The Jesuits who built the so-called Guarani reductions since the beginning of 1600, demanded for a long time from the authorities of the Society of Jesus the purchase of a printing press and the sending of a brother who understood the trade. It was in the missionaries' desire to print different works translated into local languages, among them the vocabularies, which were extremely useful for all the religious who were in the midst of the task of evangelization. Without the desired authorization, hand-copied copies circulated throughout the region, in imitation of the printed letter. But the eighteenth century had to come for the missionaries themselves to build a printing press with local resources and bring to light a Roman Martyrdom and some other little book -none of them, unfortunately, reached our days-, until in 1705 the work appeared Of the Difference between the temporal and the eternal, by Juan Eusebio Nieremberg, illustrated with beautiful vignettes -most of them xylographic- and plates engraved in bronze by the indigenous people, of which two copies with small differences between them are known. One of them was part of the Pedro de Angelis collection, and when it was put up for sale it was acquired by Rafael Trelles, much to the chagrin of Bartolomé Mitre, who unsuccessfully tried to buy it. When Trelles died, when his library was dispersed in 1916, it remained in the hands of Enrique Peña, and his daughter, also a collector, Elisa Peña, donated it to the Enrique Udaondo Museum in the city of Luján. The Jesuit printing house of the Missions had ceased to function in 1727 after publishing twenty-three titles -several of them preserved in different copies-, according to the meticulous study carried out by Father Guillermo Furlong.

The towns of the Jesuit missions had their own libraries, the most notable being that of the Town of Candelaria, where the Father Superior was based. When the members of the Order were expelled in 1767, their assets were inventoried and placed at the disposal of the Royal Board of Temporalities. It is known that finally, a good part of his books -including those of the Librería Grande or Mayor, of the Colegio Máximo de los Jesuitas in Córdoba- entered the patrimony of the National Library. Some had deteriorated due to humidity problems, others were distributed among the aborigines who repaired the roofs of the library erected by the missionaries, and of those from Córdoba, a part of them was returned in its time to the Universidad Mayor de San Carlos , old name of the University of Córdoba. In the year 2000, by presidential decree, all the others brought from there, and who were in the BN, returned to that city. Since then they have been exhibited in the Historical Museum of the National University of Córdoba, taking precautions for their preservation.

As for the books collected in those years among individuals in our portion of America, the aforementioned Furlong knew how to stop at the different known libraries, some even with details of their content, formed in the 17th century in the current Argentine territory. For example, he indicated that in the city of Córdoba there were many private reservoirs about which there is information through written testimonies. Furlong himself was surprised when his study of those colonial libraries had repercussions on various other investigations; among them, that of Professor Jorge Comadrán Ruiz, who described those constituted by individuals in Cuyo in the 18th century.

We have already explained it, in the city of Córdoba del Tucumán -as it was called at the time- was the Jesuits' College, which having had a printing press in the Guarani Missions for almost three decades since 1700, in the middle of this century , demanded before Rome and Madrid the permission to acquire another press, not having any active in Buenos Aires, Tucumán and Paraguay; its ecclesiastical jurisdiction. However, such an important wish could only be fulfilled in 1764 when the 17 drawers containing all the necessary elements for printing papers arrived, installing the equipment in the Colegio de Monserrat under the direction of the printer Pablo Karrer, a German Jesuit who also arrived in said anus. Already with the necessary licences, in the two-year period from the beginning of its activities until the expulsion of 1767, the Jesuit press in Córdoba published at least four works, three of which have survived to the present day.

Returning to the 17th century, it is surprising that, in a testament of 1609, it is suggested to sell the inherited books, to sell them in Chuquisaca or in Chile… It is very clear, the trade was fluid, and the books were circulating. Among the different inventories preserved in documents from that time, we identify the Chorography of the great Chaco Gualamba, by Father Lozano, several copies of the Difference between the temporal and eternal -in Spanish editions-, and even two copies of the Peruvian Ritual in a private library Argentina, that of Gregorio Aleman, who died in 1733.

Furthermore, in 1739 an auction was made with the books that had belonged to the library of the deceased Governor of Tucumán; among other titles there was included a copy of the History of Peru, another of the History of Mexico.

In the words of Furlong, one of the most valued historians -and we will find the same thing in Torres Revello's texts, of course- in the second half of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century, Buenos Aires had an extraordinary bibliographic movement and was considered "an exceptional market for the sale of books. Already in those years, around 1760, the first bookstore in this city had been opened -a book store to the public-, under the ownership of José de Silva y Aguiar, an outstanding personality who later promoted the installation of the Children's workshop Foundlings -its regent and administrator was appointed-, the first active printing press in Buenos Aires, although there is numerous evidence that would prove the previous operation of some small and rudimentary private press from which loose sheets with dates barely prior to 1780 would have come out. It is true that the printing press began to operate attached to the House of Foundlings - the sale of its printed productions helped pay for the humanitarian work of said Cradle of orphans - and thus it was approved by royal decree signed by Carlos III in 1782.

Title page detail. Representation of the Cabildo, and residents of the city of (...) printed in the Real Imprenta de los Ninos Expósitos (1781). Sample of the Saavedra Historical Museum. Photography: in Expósitos. Typography in Buenos Aires. 1780 - 1824. By Fabio Ares. General Directorate of Heritage and Historical Institute. Buenos Aires. 2010.

With regard to this establishment, let us say that it began its march around 1780, incorporating other sources of income to its printing activity, such as binding, the manufacture and sale of blank books -as well as inks- for merchants and public offices, and the sale of books brought from Spain. Being Silva and Aguiar his administrator, he was allowed to open a book store. Replaced this due to mismanagement, shortly before leaving office his successor, Alfonso Sánchez Sotoca, proposed in 1788 to stock the book store, "such as Arts, Daily Exercises and other similar ones of little cost and a lot of output, as all booksellers have , which is what keeps them.”

That printery of the Foundlings had begun its activity when Buenos Aires had an estimated population of about 23,000 inhabitants; Its objective was to meet the demand for printed works - loose papers, booklets and books - from the entire Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, which included the current territories of Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay and Uruguay, perhaps some two hundred thousand people. When the first printing press was installed in Mexico, that city had fifteen thousand inhabitants, and when the same thing happened in Lima, the local population did not reach ten thousand.

With the documentation available, several historians devoted themselves to shedding light on the first productions of this press. His first administrator, the aforementioned Silva y Aguiar, reported in his accounts the volume of the published forms, which would have always indicated an amount lower than the real amount - suspicions that led to an intervention ordered by the Viceroy; among others, almanacs and guides for 1781, 2,280 copies; catechisms, 13500; counting boards, 2676; catons (1), and primers (2), 65354 in four editions. The Gazetas that arrived from Madrid and Lisbon were also reproduced, 1,458 copies were rendered in the first report by Silva and Aguiar. The sale prices of each work were as follows: Almanacs and Guides, 3 pesos; Catechisms, 2 pesos; the first Gazetas, 12 reais (equivalent to 1.5 pesos); counting boards, 5 reais; booklets, 6 reais, bound and retail, double; and catones, 3 pesos. Of course, not all the works were sold, leaving a remnant of prints still unreleased. For example, as of October 31, 1782, of the Pastoral Letter of the Bishop of Córdoba (Fray José Antonio de San Alberto), whose edition comprised 41 ½ dozen (498 copies), only 28 copies had been sold by the same date”.

Willing to benefit the Home for Foundlings created at the same time, the authorities granted their printing company the exclusive privilege of selling books for primary education - catons, catechisms and primers - for ten years. In compliance with this order, Customs was instructed not to allow the entry of these booklets from Spain and so that their departure was not authorized; although in light of the known claims, the books continued to arrive and sell at prices lower than those published by the foundlings' press.

As for the management of Silva and Aguiar, the truth is that the charges filed were annulled and in 1789 he returned to direct the printing press, now as a tenant, associated with his guarantor, Antonio José Dantas, until he presented his resignation at the end of the 1794, succeeded by Dantas himself, who was neither a bookseller nor a printer, but who was able to carry out the business supported first by a new partner, Francisco Antonio Marradas, and later by the former printer, Agustín Garrigós, who finally leased it in October 1799 and for a term of five years. He was succeeded by Juan José Pérez, also for five years, after beating him in the public auction with a higher offer. It was Pérez who was responsible for publishing the numerous pages related to the defense and reconquest of Buenos Aires and Montevideo against the English invaders. The events of May 1810 found the determined patriot Agustín Donado at the head of this printing press.

Among the bibliophiles active in the times of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, Benito Mata Linares stands out, who arrived in Buenos Aires around 1787, dedicating himself to gathering works and historical papers forming a large group that is now preserved in the Library of the Academy of the History of Madrid. Another who knew how to build his library was the Governor of Buenos Aires, the Spaniard Juan Manuel Fernández, who demanded a printing press from Madrid for this city, which finally arrived from the city of Córdoba at the initiative of Viceroy Juan José de Vértiz; It was the printing press that the Jesuits had run in 1764 and which, expelled in 1767, had remained inactive in the Colegio de Monserrat.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the most popular literary gatherings in Buenos Aires were held in the house of the Spaniard Juan Matías Gutiérrez, who formed an important library, inherited by his son Juan María.

The book trade between 1810 and 1829.

The stores -most of them not yet specialized- offered local and imported books, loose sheets and printed brochures, sheet music and newspapers. They were sold like this in stores, pulperías, business and private houses, inns and, as we said, in the home of Foundling Children, where their printing press worked. For example, Jaime Marcet's store-bookstores -he had two premises, in which he gave preferential attention to the sale of books- offered through advertisements in La Gaceta Mercantil -a long-standing newspaper that began in 1823- "a series of printed matter -many of them were national publications edited in a few sheets- which today are bibliographical pieces of important value” -according to Alejandro E. Parada in his study The world of books and reading during the time of Rivadavia. Marcet promoted in another advertisement, almost a hundred titles in a single list; he also promoted subscriptions and raffles with books as prizes.

As soon as the revolutionary process of May 1810 had begun in Buenos Aires, the Public Library had been created with a wonderful contribution from individuals; among them, a bookseller installed in this city, a certain Agustín Eusebio Favre, even donated books. Before, he had sold medical books to the Women's Hospital... Another mention of the book trade even in colonial times. In the first two months, four thousand volumes were collected thanks to the benevolence of neighbors, such as Canon Luis José de Chorroarín, who handed over his personal library; to Monsignor Azamor y Ramírez, now deceased, who had donated it in 1795 to integrate the future public library, and to the measures adopted by the Board, which confiscated the library of the royalist bishop of Córdoba, Antonio Rodrigo de Orellana, a Jesuit heritage. Reading and education went hand in hand, and in the first government measures, the Patriotic Junta also set about recovering the educational power of the Colegio San Carlos, converted at that time into a troop barracks.

With the same zeal for primary education, in 1815 the authorities commissioned the Foundling Children's Press to publish books, catechisms, primers and counting tables "for the help of poor children"; for them the cost was absorbed by the public coffers, while for the others, each family had to pay the price indicated by the printing press.

The truth is that, run by administrators and tenants, the Foundling Press continued to publish well into the 1820s, though by then its presses and other accoutrements were increasingly exhausted, and its coffers were suffering from competition from other publishers. printers active at the time in Buenos Aires. Finally, the government decided in 1825 to pass it under the control of the State, appointing its staff and changing its original name to the State Printing Office.

Regarding the number of copies that were printed of a title at that time -we have already mentioned the items printed in the first years of the Foundling Children's workshop-, the notice published by the Juan Manuel Ezeiza bookstore, from Buenos Aires, in The Mercantile Gazette of November 2, 1827 reporting the existence of 400 copies of Arithmetic and 300 of Grammar. They were educational texts for children, but it is the inventory data of a single bookstore

If we take from October 1823 to December 1828, we will find in the cargo manifests arriving from other foreign places, 387 drawers and 56 trunks with books. This volume arose from the orders of 72 importers; booksellers and merchants of other items. This demonstrates the keen interest in bringing printed material from other latitudes to these shores. Being Minister of Government, Rivadavia abolished the customs duties corresponding to the book and repealed the provisions that limited its entry into the country.

In the pages of La Gaceta Mercantil books were offered "wholesale for export to Chile or Peru"; interested persons -indicated the notice- “will find the most appropriate collection to said countries at the most equitable prices”. The same bookstore offered the service "of bringing from Europe the works that are designated as accurately and as soon as possible." (In a notice published December 4, 1828). Similarly, another merchant, Guillermo Dana, promoted his management to bring books from Paris in Spanish, English, French, Italian or Latin, and even offered a catalog of books in the aforementioned languages, indicating that it was not a fortuitous action, but of an organized business with solvency and knowledge.

Notice published in the newspaper "El Argos de Buenos Ayres" on Saturday, June 16, 1821. Copies are offered for sale of the Report ordered to be published by the Honorable Board of Representatives.

Rafael Alberto Arrieta recounts in "The city and the books" that in 1825 the seventy-eight bound volumes of "a collection of everything that has been printed in Buenos Aires from June 26, 1808 to the present day" were offered for sale.

The advertisements show a great commercial activity with books arriving from different countries, some with lists of the most outstanding titles, and others more generic, but which also indicate the high volume operated. For example, the first lithographic house set up in Buenos Aires, owned by Frenchman Jean Baptiste Douville and his fiancee, Miss Pillaut Laboissière, published two notices reporting the arrival of crates containing some 1,200 books from Europe. And there were numerous subsequent advertisements that offered some titles, published by order of booksellers and also merchants from other branches, individuals, auction houses and printers. Regarding the latter, Alejandro E. Parada dwells on that of Esteban Hallet, indicating that they not only officiated as printers, but also were potential places for the sale of printed matter, newspapers, and books.

The activity was so extensive that he even summoned an English bookbinder; newly arrived, in 1825 he promoted his activity in the newspaper El Argos of Buenos Aires.

There were even circulating libraries, whose owner wrote a catalog of the books in existence and subscribers could withdraw the desired titles for reading, a modality that continued over time. Apparently, the first was that of Ortiz, a bookseller dedicated to works in Spanish, located on Potosí street. Some time later, the great Marcos Sastre bookstore applied this technique.

The historical studies consulted indicate that, at the end of Rivadavia's presidency, the Buenos Aires Public Library (today, BN) already had around 18,000 volumes. Some years later, in the pages of La Gaceta Mercantil a debate was aired about its status; the defenders of its management lamented that, despite the force of law that it possessed, it was not possible for them to deposit a free copy of all public papers and new works. The truth is that, with the diminished economic support from the government, the Public Library suffered a strong deterioration in the times of Juan Manuel de Rosas. This was reflected by the French traveler Xavier Marmier, who arrived in Buenos Aires in 1850 and left his opinions in a book that, translated into Spanish, was published in 1948: "The public library -Marmier wrote- where Rivadavia had collected twenty thousand volumes, and at the same time which earmarked an annual rent, has been stripped of the subsidy and left to the rats.” (3) That traveler also extended his gaze to the book stores, whose owners, for fear of compromising themselves before the eyes of the federal authorities, had significantly reduced his stock. This problem afflicted them from the beginning of the Rosas government; This is demonstrated by a chronicle by the Frenchman Arsène Isabelle who, amazed, narrated an episode motivated by a new work whose title I do not remember - that is how he recognized it. That title was part of a book import; the importers were imprisoned, and seized all the books, they fed the bonfire lit in the public square in front of the Cabildo. (4)

In Rivadavia's time, a large number of printed matter, several important books, and a profuse and heterogeneous variety of pamphlets, edicts, decrees, manifestos, proclamations, etc., were published, dealing especially with political and conjunctural issues. The various ideological, moral, religious and economic confrontations are manifested in the printed matter of the time. Lawsuits between individuals were aired on printed sheets, a modality that spread during the Rosas government.

In the pages of La Gaceta Mercantil we find a variety of notices referring to the world of books. In some it was indicated: those who want to sell, must go to that address. Titles were sought, volumes to complete collections, and we even located the very interested party who dared to pay above his market value. Texts were even published demanding the return of books. And even advertisements were identified with "book bargains", or "burns", in which they were sold at very affordable prices.

Very painful in our eyes, advertisements were also published with printed offers "per ream at a very comfortable price and suitable for wrapping" -surely, the result of the failures in sales. Some time later, when the ships of the French squadron blocked the port of Buenos Aires in the midst of the Rosas government, the scarcity of paper forced them to use printed sheets more emphatically to wrap the merchandise. The presence of more bibliophiles would undoubtedly have saved them from this infamous fate. All antiquarian booksellers have even seen bindings that use this paper on the endpapers with vintage handwritten annotations.

Maps, plans and nautical charts, globes and "magic lanterns" were also offered and demanded through newspapers through advertisements.

With the fall of the Hispanic regime in America, the colonial handwritten documents remained in the possession of viceregal officials and in the middle of the 19th century they were incorporated into private collections, they reached the tables of publishers -Pedro de Angelis was one of them-, or they traveled into European scholarly circles.

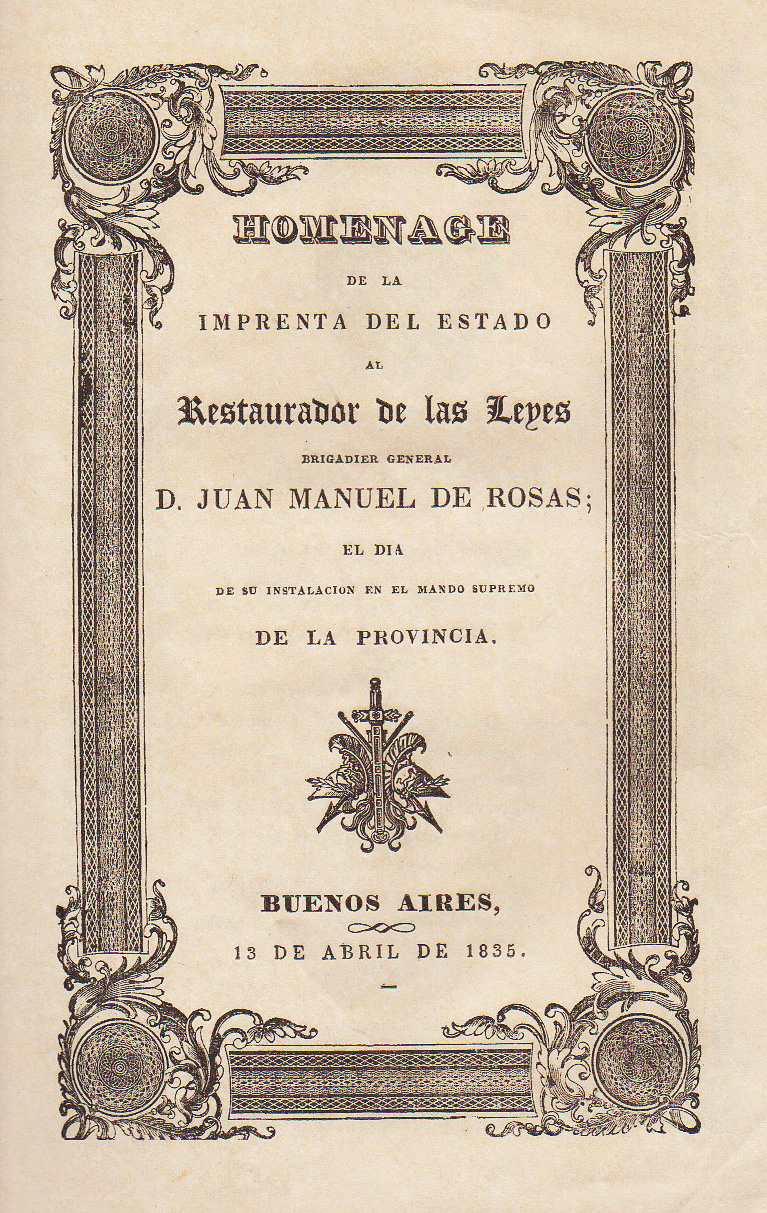

In times of Rosas

During the long period that Juan Manuel de Rosas governed the city and countryside of Buenos Aires, and a good part of the Argentine Confederation marched at his own pace, or against his own pace (from 1829 to 1852, with an interregnum between 1832 and 1835, although with a strong presence of their political force), the intellectuals branded as unitarians staged an important exodus, having to emigrate to Uruguay, Brazil, Chile and Bolivia, especially. A clear example of that situation is that of Marcos Sastre, owner of the famous Argentine Bookstore that had to quickly liquidate its stock after the closure in 1837 of the Literary Hall that worked there. This measure of the Buenos Aires government marked the beginning of a more severe policy of control over intellectual activity, identifying loyalists and adversaries: federal and unitary; process that was definitively consolidated after the defeat of the "insurrection of the free people of the South" in 1839.

Among the houses dedicated to the sale of books opened in those years, we find the College Bookstore, created in 1830; the Central Bookstore, by Lucien; that of Teófilo Duportail -who bought Sastre, and then dispersed with the sale of the latter-; that of Ezeiza, or Eseiza, already mentioned; that of José Ocantos and that of Pedro Leverf, a Frenchman who couldn't stand the smell of tobacco.

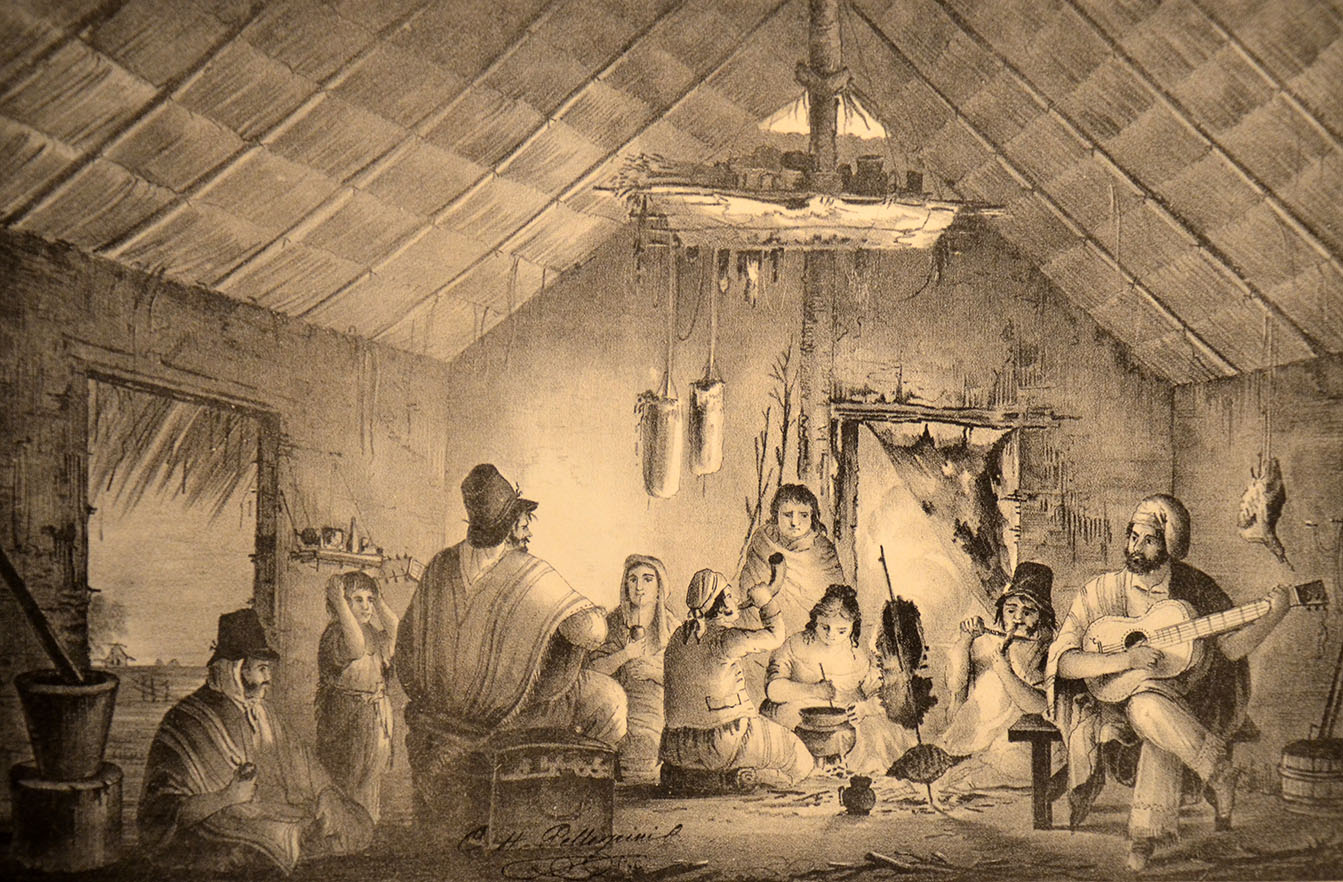

Lithograph of one of the most beautiful albums published in Buenos Aires. The artistic work was carried out by Daufresne and Isola, and was stamped in the Lithography of the Arts, by Aldao, in 1844.

Some printing presses and lithographic houses were also dedicated to the sale of books, while they focused especially on marketing their productions with varying luck. César Hipólito Bacle, with the title of State Lithographer, announced his collection of portraits Fastos de la República Argentina with notebooks of four portraits per delivery, each with his biography. But the almost total lack of subscribers made the initiative fail. Only the official purchase of some five hundred plates with the figure of Rosas promoted his mission in 1830. In those years he also published the portraits of various public figures, many of them paid for by the official coffers, always to distribute among the population for propaganda purposes. governmental. In 1841 the Savoyard Carlos Enrique Pellegrini brought out the album Recuerdos del Río de la Plata, a work of great quality, made up of twenty plates. Luis Aldao also published albums of great iconographic value, illustrated by Carlos Morel, Albérico Isola and Julio Daufresne. Another unsuccessful experience was that of Arzac with his printing press, which in 1844 began the publication of a Gallery of Illustrious Contemporaries. Each biography consisted of a 16-page booklet plus the engraving of the character made in the Lithography of the Arts: it ceased with booklet No. 4 due to lack of subscribers. Willing to overcome these pitfalls with another source of sales, in his Litografía de las Artes, Gregorio de Ibarra annexed a bookstore.

Let us return to the great Genevan lithographer, César H. Bacle, and his complaint of plagiarism against a colleague, Arístides Hilario Bernard, who had published a series of lithographs of Lima costumes in 1834. Bacle accused him in court of plagiarism, of operating a lithographic house without proper license and also of using the state emblem without permission. That episode allows us to confirm again the trade of printed works with Peru.

Bacle's workshop produced important works, some resounding economic failures -such as the Cattle Brand Registry, which only obtained eight subscribers-, and many of them of enormous importance for the political propaganda of the federal cause. However, Bacle fell into disgrace and the government of Juan Manuel de Rosas shackled him and imprisoned him for many months, until very ill, he was released to die a few days later. This episode was central in the conflict with France that led to the naval blockade of the ports of the Argentine Confederation.

In the government of Juan Manuel de Rosas, a true political dispute broke out between the federal and unitary newspapers, a counterpoint that was expressed on numerous occasions in “gauchipolitical” verses. In this combat journalism, authors contrary to official opinion suffered various persecutions. Meanwhile, the great federal newspaper was El Archivo Americano -it was published between 1843 and December 1851-, written by Pedro de Angelis and personally supervised by Rosas. It was published in Spanish, English and French, and its mission was to counteract the criticism expressed by the anti-Rosista campaign deployed in numerous European media, which had the support of the exiles.

In Buenos Aires, especially, the partisan exaltation, with special mention of Rosas, his wife Encarnación Ezcurra and their daughter Manuelita, was reflected in books, brochures, printed loose sheets, newspapers, lithographs, verses and hymns and other musical expressions, and even in theater plays.

Referring to the educational field, the federal government broke with the Society of Jesus in 1841, but one of its priests, Father Francisco Majesté, secularized, worked hard in the new Federal Republican College, inaugurated in 1842. At the university level, graduates had to swear allegiance to the National Cause of the Federation. These measures found detractors and supporters; the former generally went into exile and installed the image of “rosista barbarism”. However, numerous personalities continued their intellectual work based here, forcing us to reflect today on that value judgment. We highlight among them Vicente López y Planes, Dalmacio Vélez Sarsfield, Vicente Anastasio Echevarría, Miguel Estevez Saguí, Manuel J. García, Roque Sáenz Peña, Manuel Obligado, Nicolás Descalzi and Francisco Javier Muñiz; all of them of deserved prestige in their fields of action.

In this historical confrontation, with the exile of so many readers, with diminished bookstores, and with the production of printing presses controlled by the State, the decline of bibliophiles was inevitable. For those years only two great collectors of books, documents and manuscripts are mentioned: Saturnino Segurola and Pedro de Angelis. After his death, in 1854, his heirs delivered the historical papers to the Public Library and that same year, his library was put up for sale at auction and most of the books passed into the hands of the then Colonel Bartolomé Mitre. In the early 1820s, Alexander Caldcleugh, a member of the diplomatic staff of the British legation in Rio de Janeiro who was then in the city, had observed that "there are in possession of particular curious manuscripts for which they ask very high prices and that the best private collection, known to him, belongs to Dr. Saturnino Segurola. This was not yet director of the Library.” (5)

Pedro de Angelis, for his part, managed to form an enormous collection by drawing on the circle of enlightened priests who, among other things, hoarded Jesuit manuscripts, indigenous vocabularies, and books. De Angelis also contacted the families and widows of the pilots and geographers of the colonial administration, who kept copies or originals of the maps and descriptions of the country, in addition to being closely linked to the government of Juan Manuel de Rosas, accessing the official archives. and publishing his famous “Collection of Works and Documents related to the Ancient and Modern History of the Provinces of the Río de la Plata”. Colored by suspicions about his acquisitions, appropriations and use of those papers - his quarrels against the engineer José Álvarez de Arenales, in charge of the Topographical Department of Buenos Aires, and the complaints of Father Saturnino Segurola himself, who had provided him with some of his treasures-, built a remarkable collection, which had a different destiny from that of that, already commented. After a first failed attempt with Brazil in 1846, de Angelis negotiated the sale of his library with General Justo José de Urquiza between 1849 and 1850. The negotiations continued throughout those two years, receiving strong rejection from Vicente López y Planes -advisor to the then governor of Entre Ríos-, who considered it inadequate for its intended purpose: it would be transferred to Concepción del Uruguay for the use of the students of the College created there in July 1849. The truth is that for this or other reasons -already Urquiza distanced himself more and more from Rosas-, everything came to a standstill and numerous historians severely judge Urquiza and López y Planes for this event, since the library finally left in 1853 for Brazil.

After the battle of Caseros, without the political backing of Rosas and almost in misery, Pedro de Angelis managed to get a large part of his library acquired by the Emperor of Brazil, Don Pedro II, and today it remains in the National Library of Rio de Janeiro: 2,785 printed books and pamphlets, and 1,291 handwritten documents and maps. It is known that he had already sold numerous works here before that operation, and the rest were scattered before his death in successive private sales. Only a minimal part of the documents in his collection, drafts and bibliographical notes, in addition to personal and official letters, make up the Pedro de Ángelis collection that is preserved in the General Archive of the Nation.

There were other private libraries, of course, although they did not reach the brilliance of the two mentioned. I refer to those of Manuel Moreno -brother and biographer of Mariano Moreno-; Dalmacio Velez Sarsfield; Baldomero Garcia; Eduardo Lahitte -the only one of the jurists consulted by Rosas who opposed the execution of Camila O'Gorman-; Manuel Insiarte -apparently the most important private library of the time-; Santiago Viola, who put together a large literary library; for their part, Florencio Varela and Juan María Gutiérrez, both exiled, always forged contacts to increase their libraries in an effort to keep alive “the mania of collecting American papers”, as Gutiérrez confessed to his friend Barros Arana in 1861.

Some, in the case of Antonio Zinny, devoted themselves to putting together one- or two-page publications. Buonocore qualified them well with the title of “minor print hunters”, referring to edicts, manifestos, proclamations, trades, etc. Zinny amassed a large collection of print and newspapers from South America. The latter was sold to the Central Public Library of the University of La Plata, an institution that hired him to tour the interior of Argentina and acquire more copies in an effort to expand and complete that collection. We add that Zinny was an enormous bibliographer and published numerous works that are still essential reference today.

Another hunter of minor prints was Mariano Vega, who donated his collection of the English invasions to Bartolomé Mitre -Vega had participated as a soldier in the defense and reconquest of Buenos Aires-; today it is preserved in the public library that bears the name of the former president of the Nation.

Before Caseros

With Juan Manuel de Rosas removed from the government of Buenos Aires and exiled in England, the Argentine Confederation enthusiastically received all the emigrants who had been forced to go into exile in federal times. That return, as you can imagine, was also reflected in the publishing industry and the world of books, although the country's political-institutional evolution was not a harmonious and brief process. The ups and downs and party struggles continued and there were new exiles, but the scenario was different. “All opinions have a platform”, affirmed Rafael A. Arrieta in his cited work, alluding to the current freedom of the press; although being Mitre governor of the province of Buenos Aires he closed El Nacional, a newspaper directed by Nicolás Avellaneda, for an article. Apart from these exceptions, books and newspapers circulated without obstacles and the bookstores grew in quality and quantity -in 1855 there were already eleven operating in Buenos Aires-, as well as the printing presses and publishing houses.

In the 1860s, Pablo Mota, editor and owner of the Colegio's Bookstore, distributed his Agricultural and Industrial Almanac of Buenos Aires. On the back cover of one of its issues, it advertised an extract from the bookstore's catalogue; there they were ordered by title, author, place and year of publication, number of volumes and their prices, a selection of endearing works. The bookstores published their catalogs; for example, that of Claudio M. Joly published them in Spanish and French, and received all the novelties -as announced-, literary and scientific. Similarly, Luis Jacobsen's European Library had correspondents in Madrid, Paris, London, Dublin, Leipzig, Naples and New York, and published bibliographic lists weekly in several newspapers; it also distributed specialized catalogues. It boasted of having the largest and best chosen bibliographic flow. Foreign books flowed in Buenos Aires. Jacobsen and his colleagues offered subscription services to foreign newspapers and it is said that some magazines had more subscribed readers in Argentina than in their cities of origin.

Advertisement for the Peuser Almanac for the year 1898. Work by Jacobo Peuser, one of the great printers and publishers who worked in the second half of the 20th century in Buenos Aires. Photography: in Barracas: Multigraphic Territory. By Fabio Ares. Published in Barracas: essence of a Buenos Aires neighborhood. General Directorate of Heritage and Historical Institute. Buenos Aires. 2015.

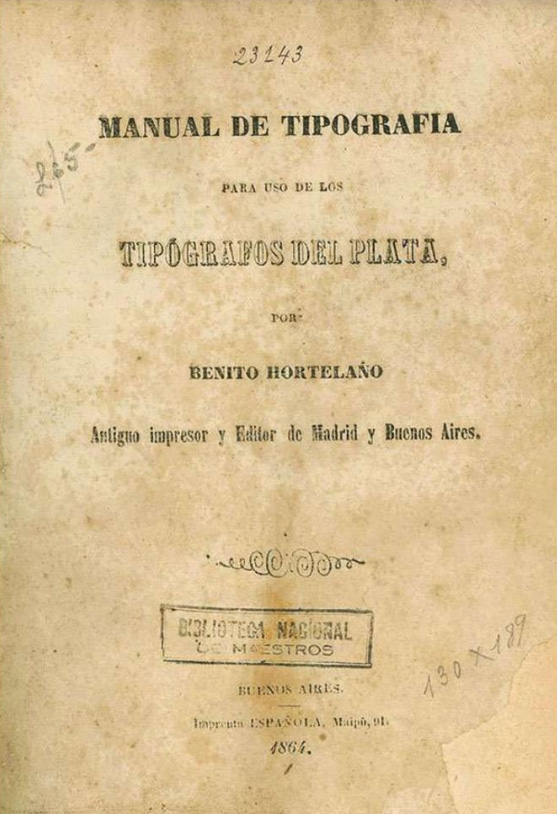

Throughout the second half of the 19th century, true colossi of printed letters emerged, among whom we can mention Benito Hortelano, Carlos Casavalle, Juan B. Igón - along with his brother, they were the new owners of the College Bookstore, where the literary gatherings renewed their parishioners with the new generations and reaffirmed their passions-, Abel Ledoux -in addition to being an editor, was the owner of the La Victoria Bookstore and sold the copy "Of the difference between the temporal and eternal" by de Angelis, printed in 1705 in the Jesuit Missions-, Ángel Estrada, Félix Lajouane, Pablo E. Coni, Guillermo Kraft and Jacobo Peuser. All of them headed successful companies, bookstores and printing presses; some come from Europe, others born in the country. His anecdotes enrich the world of books. To understand the fervor that was lived at that time, it will be enough to choose a name at random and deal with its successes and passions. A faithful exponent of the time, Carlos Casavalle (Montevideo: 1826 -Buenos Aires: 1905) opened his bookstore in this city in 1853 and except for the short one-year move to Paraná in 1860/1, it was here that he achieved his greatest success. In the back room of the Librería de Mayo, located on Calle Perú 115, Ángel Justiniano Carranza -his library is part of the BN, bought in 1902-, Manuel Ricardo Trelles -great collector, was director of the Public Archives- met in pleasant gatherings. from the Province of Buenos Aires and also from the Public Library-, Antonio Zinny, Vicente Fidel López, Germán Burmeister, and many others; Nicolás Avellaneda and Domingo F. Sarmiento even approached occasionally to animate those meetings. Among the most successful editions of Casavalle, the Historia de Belgrano written by Bartolomé Mitre sold out three runs of a thousand copies each. Buonocore recounts that, in those years, "common print runs were 300 or, at most, 500 copies." The collection gathered by Casavalle was finally acquired by the National State and today forms part of the General Archive of the Nation. A decree gave the order for its purchase to the Casa de Remates Ungaro y Barbará in 1960 in anticipation of its dispersal at auction.

Oil portrait of Bartolomé Mitre, great bibliophile, historian and former president of the Argentine Republic. Work of the painter Vitouwchesky.

Several Argentine presidents reflected their love of books in a good library, although the two most outstanding in the 19th century were those of Bartolomé Mitre and Nicolás Avellaneda, both exquisite readers. The one gathered by Mitre, the most important private library in the country, today forms part of the Museum that bears his name, and is one of the most substantial bibliographic collections in Argentina, cataloged by him, especially its Section of American Languages. With his encouragement, the organization of the Historical Museum of the Capital advanced on the right path; in 1889 the intendant Francisco Seeber named a Commission qualified to project its creation. It was made up of Bartolomé Mitre, Julio Argentino Roca, Andrés Lamas -creator of a partially accepted project, which caused his subsequent resignation-, Ramón J. Cárcano, Estanislao S. Zevallos, Manuel Mantilla and José I. Garmendia; all, except General Roca, recognized collectors. At the beginning of 1890 Adolfo Pedro Carranza was appointed with the position of director, who managed to inaugurate the Museum on August 30 of that year. With meager resources, he resorted to the support of individuals who continued to support this initiative when in 1891 it was nationalized. Previously, Mitre had donated the sword of General José María Paz, and among other gestures of detachment, he gave several objects belonging to José de San Martín to the recently created Historical Museum: the campaign chest, the band he wore on the expedition to Chile, the flag of the division of the Army of the Andes that went to Chile with Commander Cabot in 1817, and a pair of pistols.

Avellaneda, President of the Nation between 1874 and 1880, also built an important library; a good part of it went to the province of Buenos Aires to give rise to its recently created public Library. He had to sell it to pay for his only trip to Europe, destined to find a cure for an illness that afflicted him. Without remedy in the Old World and in worse health conditions, he embarked seeking to return to his homeland, but he died on the high seas at the age of 48.

Numerous other public personalities amassed important collections of historical books and documents. Among them stands out Andrés Lamas (Montevideo: 1817 – Buenos Aires: 1891), politician, diplomat, historian, journalist and academic. He joined the so-called Generation of 37 together with Alberdi, Gutiérrez, Echeverría, Sarmiento and Vicente Fidel López. A man of action, he published fervent articles against Rosas, defended Montevideo from the siege imposed by General Oribe - an ally of Rosas in Uruguay - and, being a diplomat, sealed the agreement that allowed the Brazilian and Uruguayan forces to join the army led by Urquiza to defeat the Buenos Aires governor in Caseros. In addition, a man of great lights, Lamas founded the National Historical and Geographic Institute of Uruguay, was dean of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Buenos Aires and in 1874 he worked hard to reform the General Archive of the Province of Buenos Aires , which would include a special room dedicated to the May Revolution and the Wars of Independence. At the same time, he formed an immense collection of historical papers and books - his areas of interest were very broad -, as well as numismatic pieces and works of art. He also had an important role in the organization of temporary exhibitions -one frustrated, in 1868, and the one in 1882 within the framework of the Continental Exhibition held in Buenos Aires-, antecedents that motivated him to promote the creation of a National Historical Museum, drafting even a project, an initiative that was partially accepted, as we already discussed. Personally, his treasures were finally dispersed in public auctions, although a good part of the documents were gathered in the Mitre Museum and since 1954 they remain in the General Archive of the Nation.

This network of historians, bibliophiles and collectors motivated the circulation not only of books but also of documents, whether originals or copies, a practice that spread to the interior of Argentina, Chile and Uruguay. Many of the actors knew each other personally and exchanged searches and catalogs or lists of their collections; Mitre maintained that his studies were based on the analysis of the documents and claimed to have used five thousand to write the history of Belgrano, and twelve thousand, to do the same with the life of San Martín. When the Liberator's son-in-law, Mariano Balcarce, found out that Mitre was writing the biography of his father-in-law, he gave him the hero's personal archive.

In those fervent years, there were four attempts to create a meeting and study center of history. In 1854 and at the impulse of Mitre, the Historical-Geographical Institute of the Río de la Plata was founded, which was very short-lived; they had proposed to bring together all the historical documents that were scattered - they planned to form a library, an archive, a collection of maps and a museum of antiquities - but the initiative failed. Another attempt advanced in Paraná with the Historical Institute of the Confederation, dissolved a few months after its creation. In 1872, chaired by his alma mater, Aurelio Prado Rojas, the Bonaerense Institute of Numismatics and Antiquities was born. Eight years later, Prados Rojas died in an accident and the institution fell into a lethargy from which it emerged only in 1934; Today his saga continues. In 1893, again driven by that desire to save from oblivion all historical documents -manuscripts and printed- preserved by its members, the new Board of Numismatics took shape, the germ of the National Academy of History, created in 1938. They met in the family homes of Bartolomé Mitre, Alejandro Rosa and Enrique Peña. In those years, as Irina Podgorny has explained in various works (see Bibliography), the history and creation of museums continued to be linked more to private efforts than to a State policy aimed at safeguarding “national glories”.

In the same line of analysis, Pablo Buchbinder affirms, the delay in the constitution of an administrative and archival apparatus of the State is what determined that all these essential elements remained in private hands. So much so, we continue with this researcher, that the same historians were the ones who sought to create an "institutional and organic apparatus in the sphere of the State where the practice of history could be developed." (6) The Public Archive of the province of Buenos Aires and the Public Library were nationalized in 1884, and twenty years later its organizational shortcomings continued to be a source of complaint among historians, lacking the cataloging of its collections.

At the end of the century, as director of the National Library since 1885, Paul Groussac took special care to organize its heritage, doubled the number of collected works, and published the magazine La Biblioteca with a new, more rigorous and critical look at documents. history and its study. Groussac was a protagonist in the process of creating a school of history professionals, far removed from the practices in force in the second half of the 19th century. This school of thought derived already entered the new century in the so-called New Historical School.

The passion for books and historical documents not only flourished in Buenos Aires; we find important references from private libraries in the rest of the country, for example, in the province of Salta. Good reservoirs were formed there, among them, those brought together by Casiano Goytia, Juan Martín Leguizamón and Mariano Zorreguieta. Together they published in 1872 the first book printed in that province. But the great bibliophile from Salta was Gregorio Beéche, who formed an exceptional library that accompanied him in his various homes until he settled in Valparaíso. Beeche frequented Alberdi, Sarmiento, Mitre and other personalities. In the last years of his life, he offered his books and documents for sale to the National Library of Buenos Aires, but nothing happened, and that treasure found its final destination in a public Library in Santiago de Chile. Benjamín Vicuña Mackena cataloged it and for us, his work continues to be a bibliographic reference work.

In this universe of books we want to bring to mind the name of another great bibliophile, but with a very low profile; we are referring to Pedro Denegri, a member of French bibliophile societies, who had his copies illustrated with originals by artists and writers, turning them into unique copies. He started the collection of it at the end of the 19th century. He browsed and enjoyed his books with his mittens on. Denegri visited all the bookstores in Buenos Aires and, of course, he was a friend, as well as a client, of many of their owners. When he died in 1932, his brothers complied with his will: that treasure was delivered to the National Library.

Throughout the last half century of the nineteenth century, the first “antiquarian booksellers” emerged in Buenos Aires, standing out as the most representative, Laureano M. Oucinde and Carlos Alberto Guida, the latter Italian, the other Spanish. Oucinde founded his bookstore "La Riojana" in 1877; he arrived in the country on a honeymoon and having decided to settle here, he commissioned his personal library gathered in Spain. That was the initial inventory of his undertaking. He then busied himself with bringing rare books and old out-of-print editions. A sailor by profession, he was a voracious reader; he is told that, if they chose a new book for him, he would not sell it before reading it. Among his clients we find Bernardo de Irigoyen, Onesimo Leguizamón, Aristóbulo del Valle, Miguel Cané and Alberto Navarro Viola, an exquisite bibliophile and art collector, who is remembered for his Bibliographic Yearbook of the Argentine Republic. The crowd from La Riojana pulled out chairs to the sidewalk and invaded the street; when they heard the bugle of the tramway, they momentarily cleared the tracks and after their passage they returned to the animated chats. This was the case until in 1884 Oucinde closed his bookstore.

Julio Suárez, one of the great antiquarian booksellers of the 20th century, worked as a salesman in Carlos Alberto Guida's house. Born in La Coruña in 1901, Suárez arrived in Buenos Aires as a stowaway and here discovered his destiny: in 1914 he opened his own bookstore and became an expert. His catalogs of American books published in three volumes (1933, 1935 and 1939) are unsurpassed reference pieces for the Argentine bibliophile. The most outstanding readers of the time arrived at Julio Suárez's “Cervantes” bookstore: José Torre Revello; the brothers Alejo and Alfredo González Garaño; Rafael Alberto Arrieta; Emilio Ravignani; Antonio Santamarina; General Agustín P. Justo; Ernesto H. Celesia; José Luis Busaniche and many others. But we are already in the new century, a topic that we will address in a future installment.

Ready to conclude this look at such an extensive period of time, we turn to the voice of Rubén Darío who wrote in the Spanish capital: "In Madrid there is no house comparable to those of Peuser, or Jacobsen, or Lajouane."

Grades:

1. Catones: books containing short sentences and short paragraphs to train beginners in reading.

2. Primer: Brief and elementary treatise on a trade or art.

3. Cited by Domingo Buonocore: Books and bibliophiles in times of Rosas. National University of Cordoba, 1968, p. 27.

4. Quoted by Rafael A. Arrieta: The city and the books. Bibliographic excursion to the Buenos Aires past. Buenos Aires, College Library, 1955, p. 67. Arsene Ysabelle: Voyage a Buenos-Ayres et a Porto-Alegre (...) From 1830 to 1834. Havre, 1835, chap. VII.

5. Rafael Alberto Arrieta: Ob. cit. 1955. P. 47. He cites the work of Alexander Caldcleugh: Travels in South America, during the years 1819-20-21 (London, 1825).

6. Pablo Buchbinder: Private links, public institutions and professional rules in the origins of Argentine historiography. In «Bulletin of the Institute of Argentine and American History “Dr. Emilio Ravignani”. Third series, no. 13, 1st half of 1996.

Bibliography consulted:

Ricardo N. Alonso: Libros, libreros, bibliófilos y otras disquisiciones. Salta. Mundo Editorial. 2018.

Archivos y colecciones de procedencia privada. Comisiones especiales y de homenajes. Archivo General de la Nación, Departamento Documentos Escritos. 2016.

Fabio Ares: Foundlings. Typography in Buenos Aires. 1780 - 1824. General Directorate of Heritage and Historical Institute. Buenos Aires. 2010.

Rafael Alberto Arrieta: La ciudad y los libros. Excursión bibliográfica al pasado porteño. Buenos Aires. Librería del Colegio. 1955.

María Élida Blasco: Comerciantes, coleccionistas e historiadores en el proceso de gestación y funcionamiento del Museo Histórico Nacional. En Internet.

Jorge C. Bohdziewicz: Historia y bibliografía crítica de las imprentas rioplatenses. 1830 – 1852. Instituto Bibliográfico “Antonio Zinny”. Buenos Aires. 2008 y 2010.

Pablo Buchbinder: Vínculos privados, instituciones públicas y reglas profesionales en los orígenes de la historiografía argentina. En «Boletín del Instituto de Historia Argentina y Americana “Dr. Emilio Ravignani”». Tercera serie, núm.13, 1er semestre de 1996.

Domingo Buonocore: Libreros, editores e impresores de Buenos Aires. Buenos Aires. El Ateneo. 1944.

Domingo Buonocore: Libros y bibliófilos en tiempos de Rosas. Córdoba. Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. 1968.

Jorge Comadrán Ruiz: Bibliotecas cuyanas del siglo XVIII. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Biblioteca Central. Cuadernos de la Biblioteca Nro. 2. Mendoza. 1961.

Fermín Chávez: La cultura en la época de Rosas. Buenos Aires. Edicione Theoría. 1973.

Guillermo Furlong: Bibliotecas argentinas durante la dominación hispánica. Buenos Aires. Ed. Huarpes. 1944.

Guillermo Furlong: Historia y bibliografía de las primeras imprentas rioplatenses. 1700 – 1850. Buenos Aires. Editorial Guarania. 1953.

Enrique de Gandía: Mitre Bibliófilo. Buenos Aires. Institución Mitre. 1939.

Ramón Gutiérrez: Las bibliotecas de las misiones jesuíticas. Consideraciones sobre la de Candelaria. En “Investigaciones y Ensayos”. N° 54. Buenos Aires. Academia Nacional de la Historia. 2007.

María Lía Munilla Lacasa: Celebrar y gobernar. Un estudio de las fiestas cívicas en Buenos Aires, 1810 – 1835. Buenos Aires. Miño y Dávila Editores. 2013.

Sofía Rufina Oguic: Una extensa amistad. Bartolomé Mitre y Adolfo P. Carranza. En Investigaciones y Ensayos. Núm. 61. Academia Nacional de la Historia. Buenos Aires. 2015.

Alejandro E. Parada: El mundo de los libros y de la lectura durante la época de Rivadavia. Una aproximación a través de los avisos de La Gaceta Mercantil (1823 – 1828). En “Cuadernos de Bibliotecología N° 17”. Buenos Aires, UBA, 1998.

Alejandro E. Parada: Los libros en la época del Salón Literario. El catálogo de la librería argentina de Marcos Sastre (1835). Buenos Aires. Academia Argentina de Letras. 2008.

Irina Podgorny: El argentino despertar de las faunas y de las gentes prehistóricas. Coleccionistas, museos y estudiosos en la Argentina entre 1880 y 1910. Buenos Aires. Eudeba/Libros del Rojas. 2000.

Irina Podgorny y Margaret López: El desierto en una vitrina. Museos e historia natural. México. Limusa. 2008.

Irina Podgorny: Mercaderes del pasado: Teodoro Vilardebó, Pedro de Angelis y el comercio de huesos y documentos en el Río de la Plata, 1830-1850.

Francisco Asín Remírez de Esparza: El comercio del libro antiguo. Arco Libros SL. Madrid. 2008.

Josefa Emilia Sabor: Pedro de Ángelis y los orígenes de la bibliografía argentina. Ensayo biobibliográfico. Buenos Aires. Ediciones Solar. 1995.

José Torre Revello: El libro, la imprenta y el periodismo en América durante la dominación española. Buenos Aires. Peuser. 1940.

Rodolfo Trostiné: Bacle. Ensayo. Buenos Aires. Asociación de Libreros Anticuarios de Argentina. 1953.

Carlos Vertanessian: Juan Manuel de Rosas. El retrato imposible. Imagen y poder en el Río de la Plata. Buenos Aires. Ediciones Reflejos del Plata. 2018.

Antonio Zinny: Bibliografía Histórica de las Provincias Unidas del Río de la Plata desde el año 1780 hasta el de 1821. Apéndice a la Gaceta de Buenos Aires. Buenos Aires, Imprenta Americana, 1875.