How is Catamarca not going to have the textile culture that it boasts, if it was traversed a thousand times by the Incas who inhabited its land more than six centuries ago, as evidenced by the remains located in El Shinkal and Pucará de Aconquija? Tupac Inca, tenth monarch of the dynasty, incorporated northwestern Argentina and Cuyo to the southernmost of the four regions of Tahuantinsuyo, the so-called Collasuyo, with the consequent phenomenon of transculturation in textile art, which the Incas had in turn received and reformulated from much older civilizations like that of Tihuanaco, for example. On top of this cultural amalgam, the great initiatory impulse of the new textile crafts of Catamarca arrived with the Spaniards; with its horizontal pedal looms, with its sheep and fundamentally, with its needs.

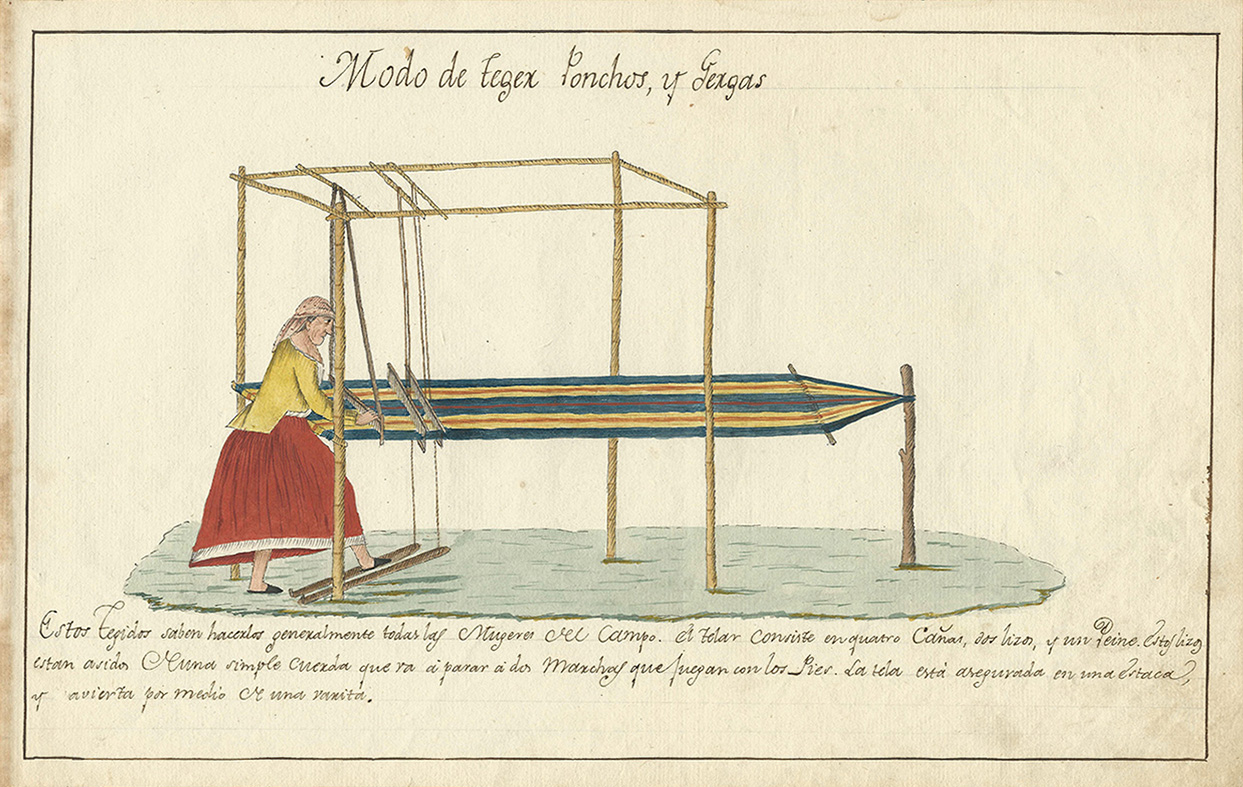

The mixture was inevitable and not without utility: the incorporation of the horizontal pedal loom was a true milestone in the textile industry of the region and it penetrated very deeply into the culture of the natives of the Northwest. This is how, in the 18th century, we find a strongly “Spanishized” society in terms of clothing. When referring to "needs", the explanation is related by Armando Bazán in his work Institutional History of Catamarca, when he states that, since the 17th century "There was no house or ranch where there was no loom (...)", because, he details , “The marginal location of Catamarca and La Rioja, with respect to the royal road that went from Buenos Aires to Peru, created a significant disadvantage for its neighbors in the supply of clothing imported from Spain, farming tools and other objects that arrived on ships registration authorized by the King for the benefit of the provinces. The prices of foreign fabrics and cloths were very expensive, and iron tools were sold for one peso per pound. For this and other reasons, the Catamarca council made a presentation to King Carlos II exposing the disadvantageous situation of Catamarca and La Rioja in the area of Tucumán. This happened on December 1, 1692. Among other complaints, the lobbyists mentioned the excessive price of foreign and farming fabrics and cloths. Thus "we are left naked", said the complainants, and having to cultivate the fields with wooden hoes. [1]

And here we must stop to think about something that, being so simple, is not considered when talking about the contribution of the Spanish loom to the history of woven clothing in America. Until his arrival, in pre-Columbian cultures, textile garments were made one by one: a warp was laid with the necessary measures for this or that garment and from there the weaving began, whether it was warp, weft, balanced , flat or with ornamental designs, but always with four selvedges or at most with structural fringes. The Spanish - most likely the Jesuit priests - introduced the concept of the piece of cloth, cutting and hemming. In short: the making.

That is why the most delicate fabrics of this region have a hem and, in the case of ponchos, a perimeter fringe. These will be made up of two identical panels facing each other in a mirror. If the telera receives an order for a poncho 1.80 m long and 1.40 wide, it will make a warp about 4 meters long and give it a width of 70 centimeters. From there, everything consists of weaving evenly until a long piece is achieved, which will then be removed from the loom and the remaining unwoven threads discarded, cut in the middle and arranged as we have already explained, to later join them with a seam that will respect a central opening forming mouth. Then he will proceed to hem the ends and will finish the work by applying the fringe that he wove on an ad hoc loom, precisely called “fringe”, all around its perimeter.

Before the conquest, the wide pieces were also woven in two cloths, but these were never identical since they were two units woven independently, with their edges enclosed by the weave (hence the name of the technique: four selvedges). The weaver used the ground or stake loom and assembled a warp with the length calculated for the piece and the width never greater than 75 cm. He weaved from end to end, without waste, he removed the cloth from the loom and went back to weaving to weave another cloth as similar as possible to the previous one. Curiously, despite coming from a common ethnic stock, while the region that concerns us now quickly incorporated the Creole loom -an adaptation of the European-, in Peru and Upper Peru (today Bolivia) it continues to this day using the pre-Columbian technique.

What the Andean communities do agree on is the use of sheep's wool, which came from Spain to share warps and wefts with the fibers of the "rams of the earth", as they called the American camelids, and in this topic Catamarca is distinguished from the rest of the NOA provinces in the use of fiber yarn or alpaca and vicuña hair to weave high quality garments. The so-called Loom Route crosses the Department of Belén from south to north. London, Belén, Puerta de San José, San Fernando, Corral Quemado, Hualfin and Villa Vil, are the towns with the highest concentration of teleras; and it is in the first two where you can currently find the most skilled "weavers" in the art of spinning by hand, with a spindle, dyeing (both with natural dyes and with industrial anilines) and mastering the Ikat technique or tied guard for their ornamental designs [2]. In London, in the patios of the artisans Selva Díaz and Graciela Salvatierra, we can see the Creole looms with their pitchforks firmly seated on the dirt floor, where family and neighbors have been working for several decades to make ponchos from a single cloth, with ikat designs, reproduction of old Mapuche ponchos, and the same thing happens in Belén, where the spirit of Doña Elinda del Valle Figueroa lives on in the hands of her daughters, who apply the teachings of this beloved telera.

Ikat Street, with the warp already dyed and the ties removed.

The textile center of the region, the Arañitas Hilanderas Work Cooperative was founded in Belén more than twenty years ago, where young people from the town are trained with a double purpose: to teach them a trade that allows them to meet their economic needs and another -perhaps intangible - but nobler still; keep alive the tradition of belichas teleras through the years in future generations.

* Special for Hilario. Arts Letters Crafts

Notes:

1. Armando Bazan. Institutional History of Catamarca. Ed Sarquis, Catamarca. Argentina, 1999, p. 71.

2. Authors' note: Ikat basically consists of tightly tying the warp threads that you want to preserve without dyeing to conform to a previously conceived design. In this way, when the wool is immersed in the dye bath, the tie will prevent the color from penetrating that sector, so that, when untying, the ornamental drawing will appear on the warp, and since the technique is warp face, It is what will be reflected in the resulting fabric when weaving, since the weft is hidden.